Magazine

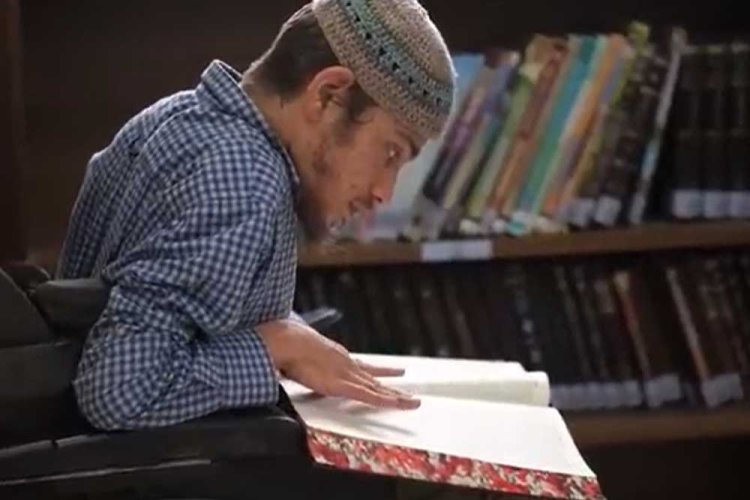

“The Torah Is My Lifeline”: Becoming a Rabbi at 25 Despite Cerebral Palsy

Born with cerebral palsy, Rabbi Ori Yitzhak Shachar refused to let physical limitations define his path. In this personal story, he reflects on Torah as a lifeline, the strength of belief, and the determination that led him to become a rabbi at the age of 25.

- Moriah Luz

- |Updated

Rabbi Ori Shachar

Rabbi Ori ShacharBy the end of twelfth grade, he had completed the Shas two or three times. “I don’t remember exactly how many,” he says with a smile. At the age of twenty five, he received rabbinical certification. Rabbi Ori Yitzhak Shachar, the man behind these remarkable achievements in Torah study, is now twenty seven, married to Shira, and learning in kollel in the city of Harish. His deep love for Torah exists alongside a complex medical reality he was born with: cerebral palsy.

“I Grew Up with the Mindset of a Regular Person”

At the very beginning of our conversation, Rabbi Shachar explains that cerebral palsy manifests in a wide range of forms, from complete independence to a lack of basic communication. He uses a wheelchair, and speaking requires significant effort, but cognitively he functions exceptionally well.

“Hashem blessed me with intellect and memory,” he says in an interview with Hidabroot. “For that alone, we must give thanks.”

He describes a childhood shaped by parents who refused to make allowances for him. “They raised me as if I could do everything. That created a deep internal struggle. I grew up with the mindset of a regular person, but with the physical abilities of a disabled individual.”

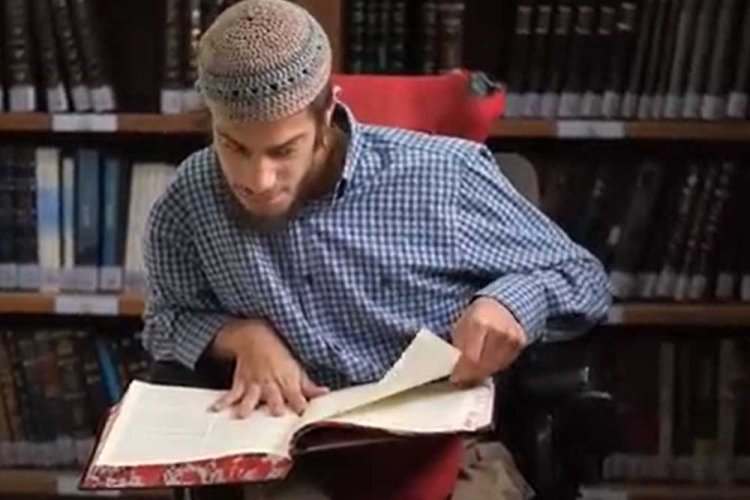

Rabbi Shachar

Rabbi Shachar Looking back, he believes that both extremes are harmful. “A child who grows up thinking only in terms of disability will never achieve anything. But treating a disabled child as if nothing is limited is also a mistake, because reality exists.”

Over time, he came to appreciate the impact of his parents’ approach. “It brought me to where I am today, but it also has consequences. Everything requires enormous effort, and I am constantly behind others. I remember wondering why getting ready in the morning took me so long. A child who knows they are disabled, yet understands they can achieve great things, will aspire upward while remaining humble.”

Torah as Oxygen

Despite the frustrations he describes, Rabbi Shachar’s achievements in Torah study are extraordinary. Asked what Torah means to him, his answer is immediate.

“First of all, Torah is oxygen. If I could not put on tefillin, I probably would not get out of bed in the morning. What logic is there in waking up knowing you are behind everyone else and part of a small minority?”

Rabbi Shachar

Rabbi Shachar He adds another layer. “If Hashem gave a disabled person the ability to learn Torah, it is not accidental. Today, some rabbis see a disabled person and immediately search for leniencies. They assume it must be too difficult. I believe we should not give up from the outset. We must understand the difficulty, but still demand everything the person is capable of.”

“I Want to Be a Rabbi”

Rabbi Shachar’s connection to Torah began early. “I was interested from a very young age, maybe around nine. But serious learning began after my Bar Mitzvah.”

Shortly afterward, he underwent surgery and was confined to his home for two months. “During that time, I mainly learned Mishnah. I completed the entire Shas of Mishnah, and it was enjoyable.”

In high school, he studied at a yeshiva in Migdal HaEmek, where he became deeply connected to Gemara learning. “In tenth grade, I decided I wanted to be a rabbi. There are not enough people who truly understand the Torah world of individuals with disabilities.”

From that point on, he focused on mastering Shas with fluency and Rashi. By the end of twelfth grade, he had completed it several times. Alongside his Torah studies, he completed a full high school diploma.

“The subject I loved most, and still specialize in, is Hebrew,” he says. “The state of Hebrew today is painful. If people truly understood how poor it is, they would cry. Errors are everywhere.”

This sensitivity affects how he reads. “When I read a book or the Torah, I read slowly and carefully. Language matters deeply to me. I follow the approach of Rabbi Mizrachi, of blessed memory, who was very precise in this area.”

“Believe in Your Capability”

Today, Rabbi Shachar has completed the Shas approximately thirteen times. When asked what advice he would give, he gently corrects the wording.

“Not advice. A suggestion. Hebrew, please,” he says with a smile.

He shares a learning technique taught by his mentor, Rabbi Yehoshua Mordechai Schmidt, head of the Yeshivat Shavei Shomron, where he studied for five years. The method involves mnemonic markings tied to page numbers, helping ideas remain anchored in memory.

At the age of twenty two, Rabbi Schmidt encouraged him to begin rabbinical certification studies. While the program usually lasts four to five years, Rabbi Shachar completed it in just three.

“I took every exam that was available, sometimes two at the same time,” he explains. “I studied intensely, and my memory helped a lot. That too is siyata dishmaya.”

He emphasizes his mother’s role. “She drove me to every exam, and sometimes had to sit with me because examiners could not understand my speech. She was fully devoted to helping me succeed.”

After completing his studies, he felt ready to build a home. About a year ago, he married Shira, who also has cerebral palsy. He speaks briefly but warmly about their marriage.

“My wife values Torah deeply and supports me completely. I call her the rabbanit, but she objects. She says she is too young for that title.”

Rabbi Shachar and Shira's wedding

Rabbi Shachar and Shira's weddingLooking Ahead

Today, Rabbi Shachar and his parents are working to allow him to take rabbinical court exams. The system currently does not permit oral exams, largely because no disabled candidate has previously requested them.

“We have begun the process,” he says. “We hope they will approve it.”

Asked what gives him strength to continue facing challenges, his response is clear and structured.

“First, never say ‘this is reality.’ Once you say that, you accept the flaw and stop striving upward. Second, never say ‘we don’t have strength.’ If something is truly important, strength exists. And third, never say ‘it won’t help.’”

He pauses, then adds, “Believe in your ability to make a difference. Alexander Bell invented the telephone. One person can start a revolution.”

“Anyone who tells me ‘don’t try’ ends the conversation with me,” he says quietly. “Going with the flow is easy. But it is the least rewarding path.”

עברית

עברית