Magazine

Ayelet Aran's Journey: From Secular Upbringing to a Religious Family

Discover Ayelet Aran’s inspiring story of returning to Judaism, navigating family dynamics, and fostering unity among children with different religious paths, while addressing the challenges and triumphs of a Ba'al Teshuvah

- Moriah Luz

- |Updated

(Illustration. Inset: Ayelet Aran)

(Illustration. Inset: Ayelet Aran)Every year, on one of the nights of Chanukah, Ayelet Aran's 11 children gather for a family meeting. A stranger looking at them would find it hard to believe they are all from the same nuclear family. The 11 siblings, all of whom have already established their own homes, are scattered across the entire "spectrum," as Aran calls it – Haredim (ultra-Orthodox), Religious Zionists, Ba'alei Teshuvah (returnees to Judaism), and secular.

This regular gathering, and the bond that exists among them, are not taken for granted. Aran, a Ba'al Teshuvah herself, has come a long way to reach this point.

"Something was missing in my soul."

"I’m 64 today. I grew up in Rishon Lezion, in a typical middle-class secular family, what you might call a 'rich girl,'" Aran begins. "My father was an engineer, and my mother was a teacher and counselor. In high school, I studied at the Rishon Lezion Real Gymnasium, alongside very intelligent and strong-willed boys. Some of these boys founded 'The Leftist Youth Group,' and they appeared to me as principled and impressive.

"Materially, I had a comfortable and good life, but I didn’t feel fulfilled," she recalls. "I felt something was missing in my soul. We’re talking about over 40 years ago, before it was the norm for everyone to be searching.

"My parents gave me the space to search for my truth, and for my part, I looked in many places. I thought maybe I’d find meaning in nature, so I went to an agricultural school. When I was in 12th grade, I participated in a volunteer program in the city of Sderot, where eighth-grade students go to development towns."

While volunteering with other friends in Sderot, some of her friends from the "The Leftist Youth Group" started returning to Judaism one by one. "Back then, there was a narrative that claimed anyone who returned to Judaism had undergone brainwashing. I didn’t accept that. I knew them. These weren’t people who would fall for brainwashing. If they returned to Judaism, there must be something to it."

She describes how she often wandered in the wheat fields surrounding Sderot and the nearby Zikim beach, reflecting on the issue. "I told myself, 'Maybe the truth you’re looking for is in Judaism. If you’re honest with yourself, you need to check there too.' A new seminary for girls had just been established in Jerusalem, and I was the first girl there."

"Who is Tzafi?"

In Jerusalem, Aran met Tzafri, who would become her husband. He belonged to the same group of friends from the "Leftist Youth Group," and he returned to Judaism alongside people who would later become Rabbi Ofer Gisin, Rabbi Oded Nitzani, and other well-known figures in the Ba'alei Teshuvah world.

"I heard the name 'Tzafi' a lot, and I was curious about who he was, since I already knew everyone except him. When they established the seminary, I came on the exact day they were setting up the furniture. I heard someone shout, 'Tzafi, put the bench here.' That’s how I met him." They married when she was 19.

The return to Judaism came with social costs and many questions and whispers behind her back. "The friends talked among themselves about how Ayelet became religious and what happened to her. It was emotionally difficult for me because these were people I loved. But I knew it was a fight for something right."

"Today, when I look back from the perspective of 45 years and see what has happened in Israel in terms of the Ba'alei Teshuvah movement, it gives me a lot of strength to know we were among the first."

How did your parents react?

"At first, it was very hard for them, and they hoped it was just a phase that would pass. My father predicted I’d have a future in the army as an officer. When I got married, they realized it probably wasn’t going to pass," she laughs.

"I chose a very demanding lifestyle, but also one that is very fulfilling and rewarding. Look at the tribe I have today, who would have believed it? We even have great-grandchildren now, thank God.

On a Chol HaMoed trip with their children, in their youth

On a Chol HaMoed trip with their children, in their youth

"To make a mistake – with confidence"

Despite the difficulty, Aran and her parents maintained a good relationship throughout the years. "In the early years of my return to Judaism, I cut ties with friends and some family members, but not with my parents. I always remained aware that 'these are your parents, and you can’t disconnect from them.' They, too, said among themselves, 'Ayelet is our daughter, and we won’t give up on her.'

"The connection with my parents was a very important process, but not everyone is like us," notes Aran. According to her, in cases where the connection with parents was severed among Ba'alei Teshuvah, the consequences were even more pronounced among their children – the second generation of Ba'alei Teshuvah. "They felt something unnatural was happening in the home. One of the reasons for the dropout phenomenon among children of Ba'alei Teshuvah is that the parents weren’t natural with them. A child strongly feels their parents."

What are the consequences of severing ties with one's family of origin?

"Usually, a parent raises their children in a way similar to how they were raised, creating a sort of generational duplication. It’s called modeling. When you don’t have the example from home, what will you use to raise your children? You start searching, listening, consulting, attending courses, and seeking rabbis. The parent hears something different from every source, and it becomes confusing.

"The first person to feel the confusion of the parent is the child. I had a wonderful parenting mentor, the daughter of the Rebbe of Lelov. She told me a phrase that has stayed with me until today: 'Even when a parent makes a mistake – let them make it with confidence.' Today, I work as a parenting mentor myself, and I see that what hurts the child the most is the parent’s lack of confidence because they feel there’s no one to defend them."

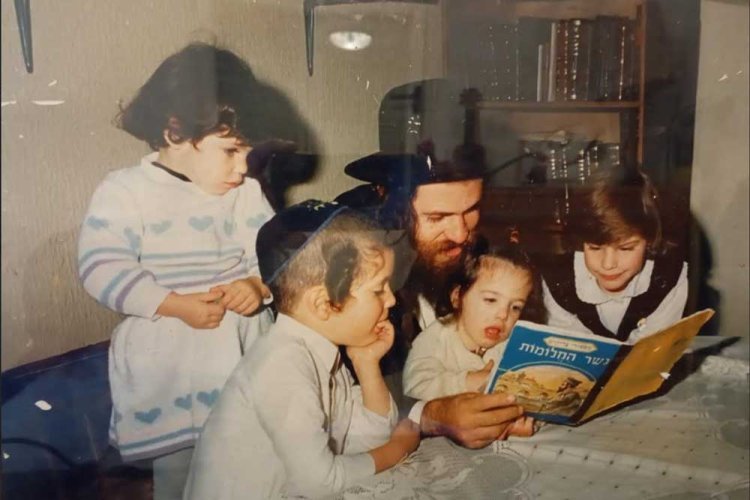

Tzafrir, Ayelet's husband, tells a story to their children

Tzafrir, Ayelet's husband, tells a story to their children

"A child needs an authentic parent"

Aran reached these conclusions, and developed her "building blocks" approach to parenting, based on her experiences in her own home. "In the early years of my return to Judaism, I raised my children innocently. I did everything I was told. But gradually, I saw that it wasn’t working with my children. They weren’t excited about lighting the Chanukah candles or the sanctity of Shabbat, or any of the other things I dreamed of passing on to them.

"At first, it was hard. It took me a while to realize something significant was missing, and it needed to be added to the components of education: naturalness. Children want an authentic parent, not a parent who recites phrases to them."

Did you understand this with your first children?

"No, it took me a while to realize this."

What was the point at which you realized something had to change?

"When I saw them starting to stray from the path and identify with figures outside the family, not with us. I told myself I wouldn’t give up on my children, and I asked myself what I needed to do to bring them back home. It was clear to me that the home was their foundation, and they needed to feel part of the family in every situation."

Even if they don’t follow your way?

"Yes, of course. That’s the point. Those who follow my way – I have no issue with their path. Back then, there wasn’t the same atmosphere that exists today, where people are encouraged to maintain connections with their children. At the time, I was quite lonely in this approach, which today I see is truly right."

"The Rebbe of Belz was the first to recognize educational processes and was among the first to start it," Aran adds. She shares that last Passover, a special gathering was held in Belz, where the Rebbe invited all the dropouts from the community. "I saw a picture. They came as they were, in their jeans."

As part of the insights she gained, Aran and her husband decided to move from the Haredi neighborhood where they had lived for many years, as part of the Breslov community, to a different neighborhood in Jerusalem. She explains that the purpose of the move was so that her children would feel comfortable coming home, even in their current state.

Did you have concerns about the spiritual state of the other children?

"No. I had a wonderful parenting mentor for many years, a very wise woman, and she always said: 'A child who wants to stray will stray even from the neighbors.' A child will always find someone to learn from if they wish to. The older I get, the more I see how true that is. What keeps children is the love of the parents, the connection, and the sense of belonging. That’s where it all begins.

"These children, who leave the home, are miserable. They lack a sense of belonging, and they don’t feel connected to anywhere. I realized I am their belonging. I am their mother, we are their parents, and I want them to feel connected to me. In the end, some of my children also strengthened themselves and returned to Judaism," she shares.

"Every child has their own process and journey in life, and as parents, we will always be there for them in that journey. And truly, I don’t have children who are ‘anti.’ My daughter, who is secular, can call me and ask, 'Mom, pray for me, I have an important exam now.' The connection with God is something they didn’t lose, and for me, that’s the key."

עברית

עברית