Magazine

From Ukraine to Israel: A Jewish Artist’s Search for Belonging

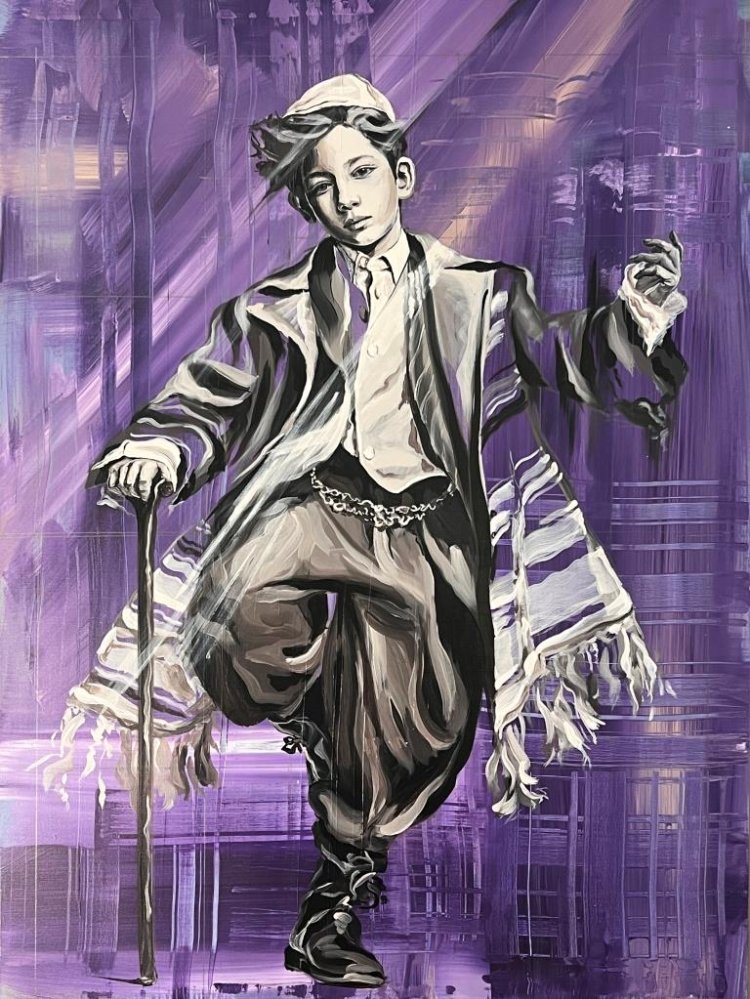

Arriving from Ukraine as a violin prodigy, Shimon Batual met disappointment instead of belonging. In a new exhibition, he shows how alienation became Judaica art, and why success abroad still hasn’t erased the feeling of being an outsider.

- Michal Arieli

- |Updated

Shimon Batual (Photo: Uri Garon)

Shimon Batual (Photo: Uri Garon)More than thirty years have passed since artist Shimon Batual immigrated to Israel with his parents, yet the sense of disappointment he felt upon arrival remains vivid.

“Even in Ukraine, in a place where Jews were afraid to keep mitzvot, we observed them without compromise,” he recalls. “We came to Israel believing that here we would finally be able to join the Jewish people in their land. Instead, the reception was a harsh awakening. Rather than being seen as Jews who sacrificed for Torah observance, we were labeled simply as ‘Russians.’ We had to fight for our place, and alongside that struggle came a deep sense of loneliness.”

Shimon Batual (Photo: Uri Garon)

Shimon Batual (Photo: Uri Garon)Batual speaks candidly, with pain still present beneath his words. Yet it was precisely this struggle and this loneliness that ultimately gave birth to a powerful artistic language. Today, as an internationally recognized artist, he presents an extraordinary exhibition that reveals not only his works, but the personal and collective story woven into them.

Antisemitism as a Way of Life

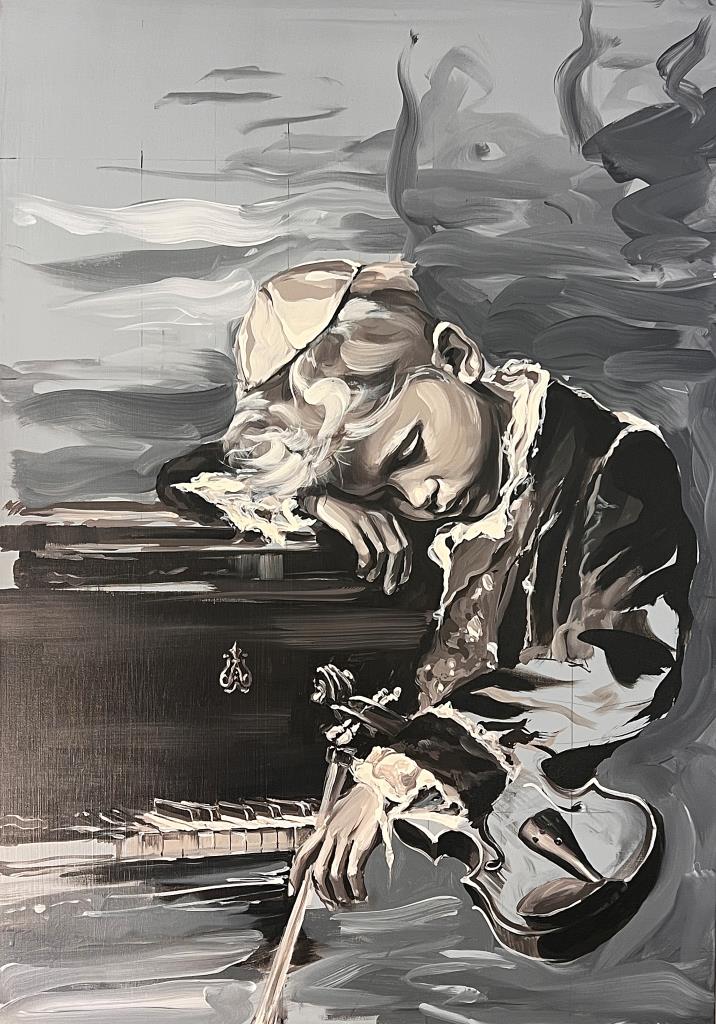

“My parents invested in my musical talent from a very young age,” Batual begins. “I started studying music at six and never stopped. I played the violin and other instruments, and our home revolved around music and art.”

He grew up with two sisters and a brother, in a family where creativity was encouraged and nurtured. “My parents invested in all of us professionally, but they placed their greatest hopes in me.”

Shimon Batual's artwork

Shimon Batual's artworkA family with four children was unusual in Ukraine, wasn’t it?

“Very much so,” he agrees. “But my father is Georgian, not Ukrainian. He grew up in a place that was not under Soviet rule, where tradition was preserved far more openly. In Georgian culture, a large family was not considered unusual.”

Judaism was central in the Batual household. “We were among the few families who celebrated Passover at home,” he says. “Every Friday night, we made Kiddush and held a Shabbat meal. We didn’t hide it, even when it could have endangered us.”

In their final years in Ukraine, their home became a gathering place. “Jewish guests would come, some we didn’t even know, just to see what Kiddush looked like. Some cried and said, ‘I remember my grandfather doing this.’ Others had no such memory at all, but everyone felt a deep, emotional connection.”

Where did you study as a child?

“There were no Jewish schools, so I attended a regular school taught in Russian and English. I never felt wanted there. Antisemitic incidents were common, and no one intervened. That was simply part of life.”

He remembers the excitement leading up to their aliyah in 1991, during the great wave of immigration. “My parents insisted that we come as one family, without separating,” he explains. “They made sure I brought my instruments with me. They constantly reminded me that although we were starting anew, we were bringing our talents with us.”

Reality, however, struck hard.

Crushed Hopes

“The first great disappointment was music,” Batual admits. “My parents quickly realized that Israel had no real space for serious artistic music. Even today it’s difficult, but back then it barely existed.”

For a time, they tried to push him to continue, but within a year he left music entirely. “The day I closed the violin case, I felt something shut down inside me. My entire childhood revolved around that instrument. Suddenly I was a child in a new country, without language, without music, standing before emptiness.”

Shimon Batual's artwork

Shimon Batual's artworkAnd yet, from that emptiness, something unexpected emerged.

“When music ended, art burst out of me. Until age thirteen, I had never touched visual art. I didn’t even know I could create, but suddenly it poured out.”

His early works bore musical names, such as Adagio and Moderato, reflecting rhythm and emotion. “Music is the art closest to painting,” he reflects. “Anyone who paints feels an inner melody, even if they’ve never held an instrument.”

Alongside creation came the ongoing struggle of immigration. “Like all new immigrants, we faced difficulties, but the greatest shock was emotional. In Ukraine, we always felt part of a people. Here, suddenly, we were ‘Russians,’ ‘Ukrainians,’ ‘Georgians.’ That label cut us off from everything we believed Zionism meant.”

Shimon Batual's artwork

Shimon Batual's artworkListen, O Heavens

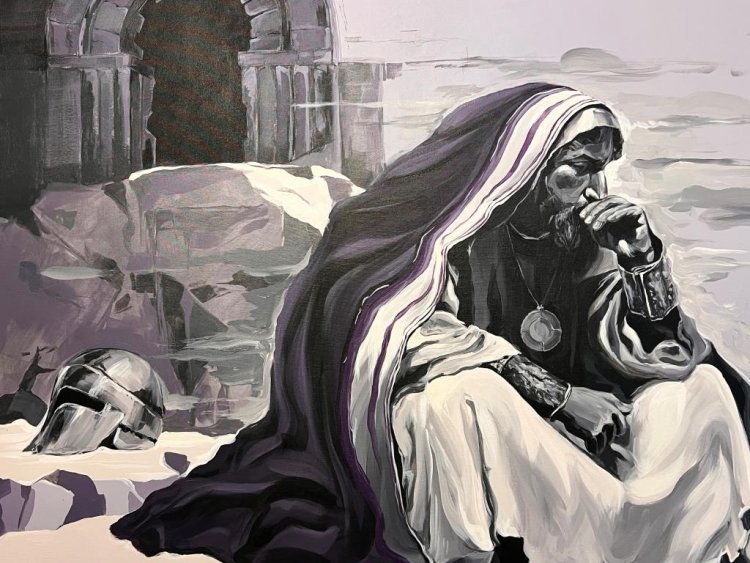

It was precisely this rupture that led Batual to focus exclusively on Jewish identity in his art. “Being Jewish isn’t only religion,” he explains. “It’s history, memory, difference. Even today, wherever I exhibit, I am always the other.”

He made a lifelong decision to paint only Judaica, but expansively. “I want my paintings to move, like music. The figures dance. The colors vibrate.”

Hebrew letters appear in his works, not as readable text, but as visual rhythm. “The letters become melody. They’re seen, not heard.”

Verses from Torah are sometimes woven into abstract forms, merging calligraphy and movement. “When meaning can’t be painted directly, the verse becomes part of the image itself.”

These days, Batual is presenting his newest body of work at the Ashkala Gallery in Old Jaffa, an exhibition two years in the making. He titled it Listen, O Heavens, and I Will Speak, the verse he read at his Bar Mitzvah less than a year after immigrating.

“There’s a powerful closure here,” he says quietly. “Jews from the Soviet Union coming home was never a given. Watching the war today between Russia and Ukraine, I understand how clear it is that our place is not there.”

He pauses, then concludes:

“Even with challenges and uncertainty, there is no doubt this is the best place in the world for us.”

עברית

עברית