Magazine

Discovering My Roots: Unveiling My Parents' Holocaust Survival

How Chana Rotenberg uncovered her parents’ hidden past and turned it into a story of faith, resilience, and spiritual heroism

- Verd Blar

- |Updated

Hannah Rothberg's Parents

Hannah Rothberg's ParentsChana Rotenberg had a happy childhood filled with trips, cheerful summer vacations, and a loving family atmosphere. She grew up in Antwerp, Belgium, the daughter of loving and caring parents, in a classic ultra-Orthodox family. She never thought that her childhood, perhaps the most “normal” childhood one could imagine, was supposed to be any different.

Unlike other children of that period, whose parents’ past hovered over them like a heavy shadow, in the Rotenberg home there were never any secrets. In fact, only years later, after she grew up, married, and became a mother, did Chana realize how much her parents, both Holocaust survivors, had sacrificed in order to create for their children a childhood as normal as possible.

Chana’s father, Rabbi Shalom Dovid Horowitz, went through all the horrors of the Holocaust in his own flesh. Auschwitz… the death marches… the stuff nightmares are made of. Her mother was also a Holocaust survivor. They never mentioned what they had gone through, not even in a single word.

“Did I know there had been a war? Yes, of course,” she says when I ask her if the Holocaust was never spoken about at home. “My father would tell many stories about what was before the war, but the term ‘Holocaust’ came much later. We knew there were no grandparents and almost no relatives, but that didn’t feel different to us, because in many families around us that was the situation. Only when I grew up and read Holocaust books I found, did I understand that there really was a Holocaust. But I didn’t connect all the descriptions there to my parents, who were strong and happy. The horrors I read about had nothing to do with the parents I knew in any way.”

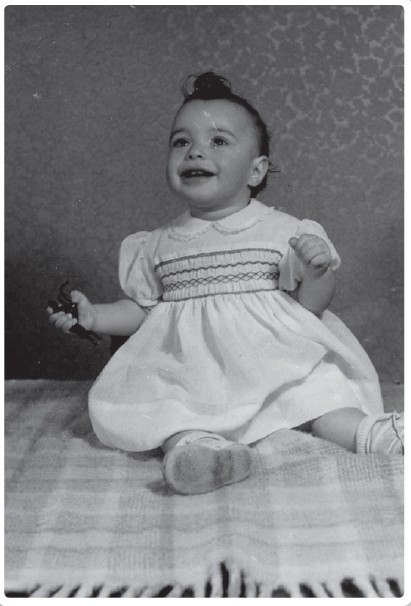

אני - תינוקת מאושרת

אני - תינוקת מאושרת“You don’t talk about the Holocaust if you want to stay sane”

Years later, after she grew up, married, and had children of her own, Chana discovered what her parents had gone through. This discovery was a turning point in her life and led her to write a book that became a bestseller, called “How Did I Not Know?”

In her book, Chana describes that innocence in simple, clear words. “We all knew there had been a Holocaust and there had been extermination, and we even knew there were camps,” she writes. “But it wasn’t really connected to us. For me it was like reading about the Inquisition – torture chambers, dark cellars, and inquisitors in demonic cloth masks…”

Unlike other homes, in Chana’s house they did not collect crumbs from the floor. Her mother did not chase her to eat “just one more spoonful of porridge,” and going on school trips that included sleeping away from home was completely routine. A totally normal and healthy childhood.

How do you explain that you didn’t know anything?

“I think my parents had tremendous heavenly assistance. Years later, after I traveled with them to Poland, I asked my mother if not telling us anything had been a conscious decision. She answered that she and my father had never had a conversation about the subject. It was simply understood to them that you don’t talk about the Holocaust if you want to raise sane, normal children. When I think about it, that is such a non-obvious decision. After all, they didn’t even have a yahrzeit date for their parents and siblings. Everything was lost, but it wasn’t a topic. Today I understand that this was the best and healthiest way to raise us. Psychology may reject such repression, but back then they had no one to consult with and no one to ask. They simply had heavenly help with that decision.”

מסע שורשים עם ההורים )קיץ 2005 ( ליד בית המדרש בגור

מסע שורשים עם ההורים )קיץ 2005 ( ליד בית המדרש בגורAs a child, didn’t you try to talk with your parents about that war?

“It’s not that we didn’t hear stories. My father told experiences from the cheder, we knew what games my mother loved when she was little, we knew there were no grandparents, and we knew that once everyone had lived in Poland, but about that war we didn’t talk. We had a kind of unspoken agreement that was very comfortable for them and for us: they don’t tell, and we don’t ask. I was a curious child, but here I felt that it was better not to ask and not to know; it was comfortable for everyone. And that went on for a long time.”

When Chana grew older, she read Holocaust books, but she struggled to connect the horrors and chilling descriptions to her parents. She also never had any desire to know what they had gone through in those days of rage. “In our eyes, everything belonged to the past,” she says.

The first time she was exposed to her father’s story was at the bar mitzvah of his first grandson. She was already a married woman, a mother to grown children, and what she heard was new to her. “My father then told about tefillin that had been smuggled into the Birkenau camp by a friend of his,” she recalls. “He asked my father, ‘What will I do with them?’ My father told him, ‘Let’s hide them,’ and so it was. Every morning a few men who knew the secret of the tefillin would put them on before that cursed morning roll call.”

“This is the first story that Grandpa told at the bar mitzvah of his first grandson. He said that every time he put on the tefillin and stood facing the cursed chimneys that spewed smoke everyone knew the meaning of, he would say to God: ‘I know that at every moment I am wearing tefillin, I am risking my life; a Nazi can pass by and shoot me. But God, I know that You are behind this smoke, and because of that I am willing to risk my life.’ And so, for eight full months, through miracles, every morning he stood and put on tefillin in Auschwitz.”

This moving story caused those present to wipe more than one tear at that event, but the big change came only a few years later, when she was exposed to her parents’ full testimony.

“I became a ‘daughter of…’ only after I already had grown children. And only then did the atom bomb that changed my life suddenly fall on my head. Suddenly I found out that my parents had gone through the Holocaust – and how!”

It was in 1994. At that time Chana’s parents took part in the great testimony project of the Spielberg Foundation. Chana says she encouraged her parents to go and testify, but it took her a long time before she decided to actually watch the tapes.

“I kept putting off watching the testimonies,” she says. “Every day I promised myself I would watch them tomorrow, but the days stretched into weeks and months. The tapes lay in my house for several months, hidden in a closet, until the Nine Days of that year. Then I decided that there would be no more excuses. I would no longer postpone watching the testimonies. With great effort I obtained a video player to screen the testimonies, locked myself in a room, closed the door, and pressed the Play button.”

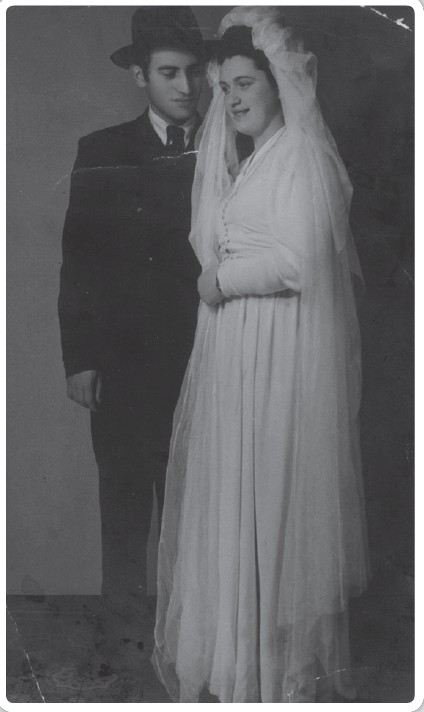

הורי בחתונתם - אנטוורפן 1946

הורי בחתונתם - אנטוורפן 1946“I heard my parents’ testimonies and felt the heavens turn over on me”

That moment, says Chana, was the moment her life changed.

“My parents’ testimony lasted nine hours. For six hours my father recounted his story, and for three hours my mother recounted her experiences and memories. During those hours I felt that the heavens were turning over on me. Everything I thought, everything I believed, crumbled. I watched my parents telling, in quiet, measured words, what they had been through, and I realized that I didn’t know them. That all their lives, my parents, strong and loving, had raised us with a mask on their faces.”

For the first time in her life, Chana was exposed to what her parents had gone through: the horrors, the extermination camps, the immense loss. For the first time in her life she heard her parents, those who had shaped her childhood, speaking with deep pain in their voices about the destruction of their home, down to the foundation. The memories were terrible, inconceivable. It was hard to connect them to the loving parents who took their children on summer trips, who sewed costumes and played with the grandchildren, and who had been a symbol of sanity and normalcy. Suddenly Chana understood, all at once, that she was second generation in every sense. That her parents, heroes of spirit, had done the impossible and given their children the childhood they themselves never had.

Tisha B’Av of that year was one of the saddest days she had ever experienced. The paralyzing shock of the discovery did not let go. “For the first time in my life, I broke the agreement that we had kept so faithfully,” she writes in her book about the days after the discovery. “‘Don’t ask’ was the agreement, ‘and we won’t tell.’ Be careful not to touch the layer of glass with which we coated your lives. Your world will continue to be round and sweet and coated in sparkling powdered sugar, and our world will keep on being silent and silent and silent… because only like this can we raise you, and only like this can you grow. And I broke the agreement… My world was no longer sugary and sweet… I no longer belonged to that world, when everything that had been built inside me over long years of trust and innocence suddenly cracked with a great, loud noise…”

The days after that, Chana says, were a turning point for her. “Watching the testimonies was the great turning point in my life. After I saw the testimonies, I decided that I had to know more, that I had to know every detail of what my parents went through in those days. I started reading books, academic articles, I took courses. I devoured every Holocaust book I could get my hands on, delved into testimonies, and simply studied the subject.”

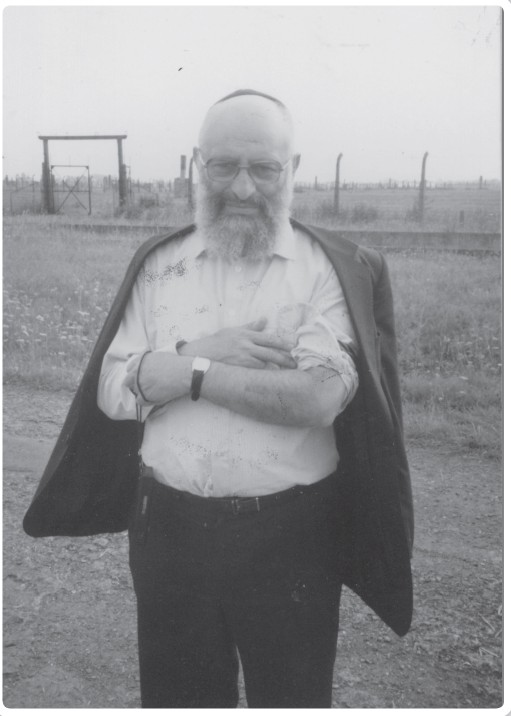

אבי בשערי אושוויץ - מראה את המספר שעל ידו

אבי בשערי אושוויץ - מראה את המספר שעל ידוHow did your parents react to this step, after years of silence and concealment?

“It was something natural and beautiful, like a river that had been blocked by a dam that slowly opens, and slowly begins to flow. It was a gradual process, even though there was no conscious decision. It’s not that they planned not to tell and then suddenly decided to share stories; it just came gradually, as they slowly began to tell what they had gone through in those years, and it was a natural and healthy process. In general, parents sharing is very important for the children so they can pass it on to future generations. I have no regrets that I didn’t listen or hear enough after my father passed away, because he told me everything.”

After hearing the testimonies, Chana persuaded her parents to travel together with their children on a roots trip to Poland. The trip was emotional but restrained, and Chana decided she wanted to go again. In 2008, the organization Nefesh Yehudi, which organizes student trips to Poland, approached her with a request to join a group of secular female students on their journey to Poland.

“At first I hesitated,” Chana relates. “I didn’t know what story I had to tell. After all, I am not a Holocaust survivor, and I also did not have the ‘classic’ second-generation childhood; I had a childhood people could only envy. No one hid bread in the attic, and my parents did not have nightmares in the middle of the night. What could I possibly give them? But when we began the trip, I was amazed to discover how much the students connected specifically to my small, ordinary stories. It was an incredible trip. They just wanted to hear more and more: about my parents, about their childhood, about their spiritual heroism and their devotion to faith during the Holocaust. Then, for the first time, I realized that I had an exceptional story.”

Darkness and light

The connection of that group of students, who were far from Judaism, to Chana’s story was powerful. For the first time, they were exposed to stories of Jewish heroism during the Holocaust, to the spiritual courage of people who risked their lives in order to put on tefillin and continue observing mitzvot under impossible conditions. The journey, Chana says, left a deep mark on them. For some, it led to an even more substantial change.

In her book, Chana tells about Miri, a master’s student who, as a result of the trip to Poland, decided to draw closer to Judaism. She became religious, married a baal teshuva, and today lives in Jerusalem, as a mother to a large family. She is not the only one who decided to come closer to Judaism after the trip. After the first journey came another, and then another, and slowly Chana understood that she had a unique story.

When did the decision to write the book come about?

“After the third trip, I realized that I had a story worth telling. The children and grandchildren also started pressing me to write down my story. At that time I began teaching about the Holocaust in in-service trainings and seminars in an organized way, adopting for myself the method of my teacher and mentor, Rebbetzin Esther Farbstein – to focus on the illuminated part, on the spiritual heroism of the martyrs of the Holocaust. It was important to me to tell a different kind of Holocaust story. Not to tell only about the camps and ghettos and gas chambers, because that is told enough already, but to raise awareness that there were also other aspects of the Holocaust. I decided that if I wrote a book, it would be different, because I wanted to reach broad audiences, including people who don’t connect to Holocaust stories. I wanted it to be a bright book, that you can read on Shabbat and come out with your head held high.”

After a search for the right author to put her story into writing, Chana found the writer Miriam Aflalo, who wrote and edited the words and stories into a stirring and emotional book. “It was very important to me that this book be different, that it focus on light and goodness,” she says. “And thank God, the connection between us was immediate. Working on the book took more than a year, which included deep interviews and intensive editing work.”

The result was the book “How Did I Not Know,” which tells her story in a non-linear narrative that jumps between Chana’s childhood in Belgium, the trip to Poland that took place years later, and her parents’ experiences during the Holocaust. It is a different kind of book in the landscape of Holocaust literature, full of warm childhood descriptions and written entirely in a loving, nostalgic tone.

“The responses I hear again and again since the book came out, even though each time in different words, repeat the same point: how much the story of the Holocaust survivors, the heroes of spirit, obligates us – those who gathered their strength after the destruction and ruin and continued life, with faith giving them power. I think this is a mission: to pass on to future generations that there was also much spirit, faith, and heroism in the Holocaust. Even though my parents never saw themselves as heroes. They simply lived, raised children, and built the next generation, giving us the happiest childhood one could possibly imagine.”

עברית

עברית