Magazine

The Unsung Heroes of the Yom Kippur War

For eight grueling days, the soldiers of Matzah Outpost stood their ground with unparalleled bravery until they received the order to surrender. Fifty-two years later, outpost commander Shlomo Ardinst shares their unyielding resistance, the harsh captivity, and the battles that continued even after returning home.

- Michal Arieli

- |Updated

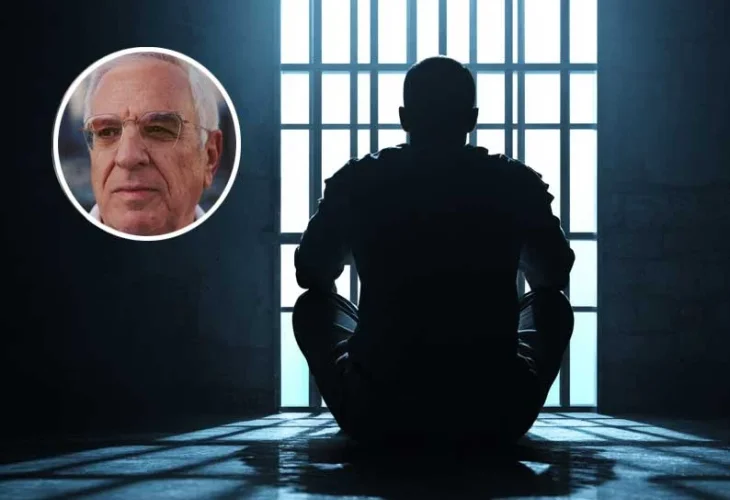

Illustration: Lawyer Shlomo Ardinst

Illustration: Lawyer Shlomo ArdinstShlomo Ardinst isn’t just another name in the list of Yom Kippur War prisoners. As the exceptionally young commander of the strategic southern outpost Matzah in the Sinai Peninsula, Ardinst symbolizes the war's spirit through unimaginable heroism. Today, he leads the 'Cities in the Night' organization supporting former IDF soldiers who were held as prisoners of war.

When Ardinst arrived at his post three months before Yom Kippur 1973, the outlook was calm, an illusion shattered when war broke out on Yom Kippur day. He recounts the story of the last outpost on the canal that refused to fall, the captivity in Egypt, and the fight for survival that persisted even after returning to Israel.

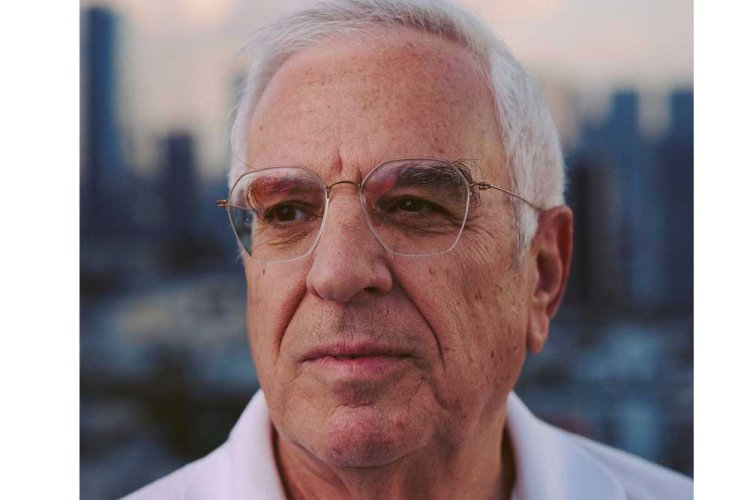

Shlomo Ardinst

Shlomo ArdinstA Sudden Shock

"When the Yom Kippur War broke, I was commanding the three southern outposts of the canal near the city of Suez," Ardinst begins. "We were stationed at the largest outpost – 'Matzah', which overlooked a strategically pivotal connection between the sea and the canal.

We had replaced another group who hadn't indicated any imminent threat. Our mood was lighthearted, with most of us close to being discharged from the army. Although quiet and peaceful, we watched the Egyptians up close, differentiating between them and even giving them nicknames.

About two weeks before Rosh Hashanah, things changed drastically. Although there weren't direct threats, there was a noticeable military buildup on the Egyptian side, with new weaponry and continuous drills. This was impossible to ignore."

Did this worry you?

"Absolutely. We constantly reported our observations to higher command, but their response was cold. The week before Yom Kippur, the Southern Command chief and his staff toured the area. They seemed surprised but reassured us afterward that it was merely an 'Egyptian military drill' set to end the Sunday after Yom Kippur, which that year fell on a Saturday. As a result, I didn't think it necessary to keep everyone at the outpost, allowing the outpost commander a holiday leave and preparing a leave schedule for others. Preparations for an Egyptian air force attack were canceled, keeping the environment calm and relaxed."

Ardinst takes us back to that unforgettable Yom Kippur: "During the break between the additional and afternoon prayers, due to the heat in Sinai, we were in bunker shelters underground with only those necessary remaining above. Suddenly, one officer told me, 'We've received an alert for immediate readiness.' Not suspecting war, I assumed it meant artillery fire. Since the Egyptian 'drill' was to end on Sunday, I replied, 'Let’s prepare for this alert after the fast ends.' But soon he returned to clarify, 'This is no drill; it’s a real alert.'"

I equipped myself and hurried to check where this fire was coming from to target our artillery. The fear was a potential Egyptian advance towards Israeli territory, akin to what happened on October 7. I identified Egyptian planes crossing the canal, triggering the first alarm in southern Sinai to alert of an air force infiltration."

Two years later, comparisons between the surprise of the Yom Kippur War and the Hamas attack on Simchat Torah continue to resurface, Ardinst notes. “In both cases, warnings were raised, yet senior leadership failed to respond adequately. The lesson is clear: when in doubt, prepare. You may be mocked, but readiness is essential.”

The Last Outpost

Matzah outpost, under Ardinst's command, was the last to withstand Egyptian forces along the canal. "Most fell on the first or second day, a few on the third, leaving us isolated and unreachable by the IDF," he recalls.

"Conditions worsened by the day. After eight days, we had suffered five fatalities and more than twenty injuries, while our ammunition was running low. Some soldiers began collapsing, as we entered the war while fasting and with a non-standard force composition. Some Armored Corps personnel fought as infantry, and reserve soldiers from the rabbinate helped organize prayers. Despite all this, we fought bravely and inflicted heavy losses on the Egyptians. A captured Egyptian officer later told me that we caused more than 150 casualties on their side. During the fighting, we even scavenged weapons from fallen Egyptian soldiers."

“Indeed, it was beyond the natural. As the years pass, it becomes increasingly clear to me that this was not achieved by our prowess alone. Our ability to survive and continue fighting for eight days defied logic and statistics. We were not a commando unit, but a force largely made up of soldiers nearing discharge. Even so, each of us gave everything we had, forming an impenetrable line of defense.

“Faith also sustained us. Verses such as ‘Some trust in chariots, and some in horses, but we trust in the name of Hashem’ echoed over the radios. There were moments that felt miraculous, such as a tank set ablaze by friendly fire, that strengthened our resolve. As Sukkot approached, we spoke of the protective clouds and organized holiday prayers in the bunker where the wounded were being treated. These acts gave us strength and helped us believe we could endure another day.”

What made you surrender after eight days?

“On the sixth night, as the seventh day approached, I realized the naval commandos would not reach us and contacted high command. Using an encrypted voice device, I reported our casualties and the shortage of ammunition. To my shock, the response was, ‘You have permission to surrender.’

Until that moment, surrender had never been an option, especially to the Egyptians. I feared what might happen if we laid down our arms, recalling the gunfire we heard after a neighboring outpost surrendered. Though it was never confirmed, I feared that everyone there had been executed.”

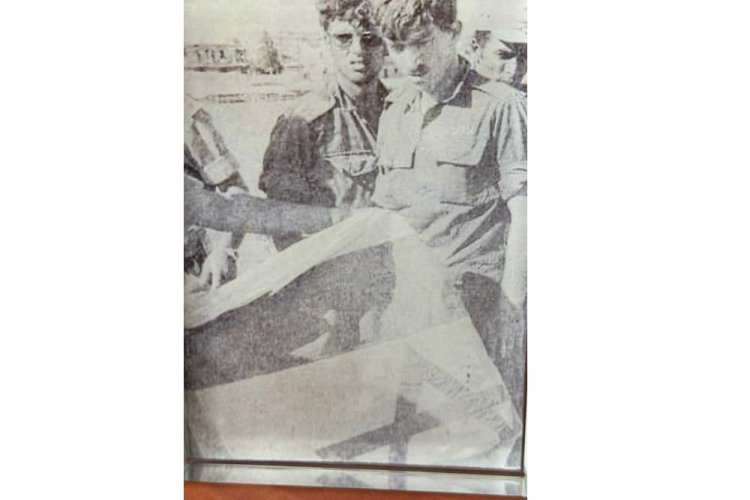

Lowering the flag during surrender

Lowering the flag during surrender“At first, I refused to surrender. But as time passed, conditions deteriorated, and it became clear that the IDF could not reach us, I was forced to reconsider. Our military doctor, about 30 years old and the oldest among us, suggested surrendering specifically to the Red Cross, hoping that media presence would offer some protection.

“On the morning of the eighth day, the Egyptians accepted our conditions. I hesitated and contacted command once more, receiving a direct order: ‘Yes, it’s a command.’ Reluctantly, I informed the soldiers that we were surrendering. Some broke down in tears, insisting, ‘We’ll keep fighting.’ I addressed the fears of the wounded, reassuring them that an agreement involving the Red Cross meant medical evacuation.

“As we began destroying weapons and burning documents, command suddenly reversed the surrender order. By then, however, the soldiers had already destroyed their weapons and lost their fighting capacity and morale. Further inquiries about how long we were expected to hold out and whether supplies would arrive produced only vague answers. At that point, it became clear that surrender was the safest option. In hindsight, that decision ensured that all of our captives eventually returned home.”

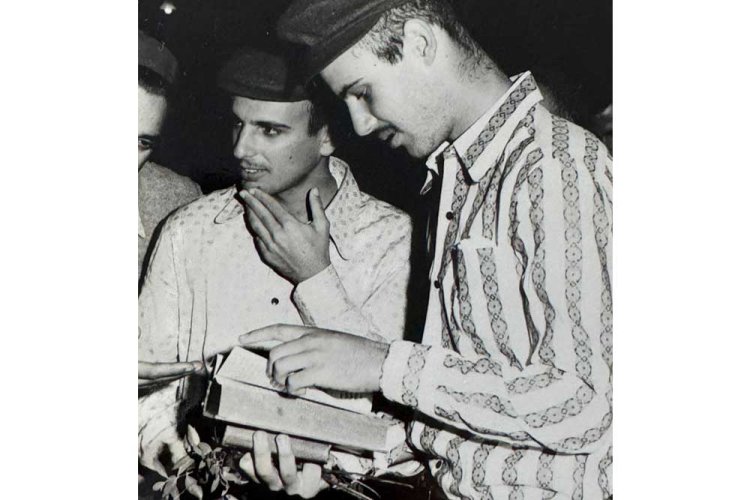

Saluting an Egyptian Officer

Saluting an Egyptian Officer"Must Survive"

What was life like in captivity?

“As an officer, I was initially detained separately, along with several pilots, each of us held in solitary confinement. We endured harsher treatment and longer interrogations, as they sought military secrets. Later, blindfolded and bound, we were transferred to a central prison. There, I remained isolated, though somewhat closer to other prisoners. Hunger and thirst were constant companions. Basic needs were often denied, and we were frequently kept blindfolded.

“The greatest challenge was maintaining my humanity and will to live. I preserved my sanity by retreating into imagination, recalling comforting moments, like enjoying my mother’s apple strudel with tea or memories from youth group activities. These thoughts helped distance me from the harshness of reality. My background as the child of a survivor strengthened my resolve. I knew I was my father’s only legacy after he survived the Holocaust without siblings, and that knowledge compelled me to stay alive.

“From the outset, I understood that captivity was another battlefield. I committed myself to clarity and resilience. After each interrogation, I mentally reviewed my statements to ensure accuracy. When given half a pita, I rationed it carefully, eating slowly to manage hunger. Emotionally, I drew strength from small acts of dignity, sweeping my cell before Shabbat with my bare hands and quietly reciting the prayers in my mind.”

Ardinst also shares a moment of emotional release:

“Toward the end of the war, Egyptian officers visited and expressed surprise at our endurance. Once they recognized my leadership role, they spoke more openly with me. Later, encounters with Egyptian university professors hinted at the possibility of peace, something that would only materialize seven years later.”

In a Cairo synagogue

In a Cairo synagogue"Transferring us to a synagogue in Cairo reflected the Egyptians’ desire to make a favorable impression abroad, presenting us as well-treated captives. They allowed us to pray there, further reinforcing the image of humane treatment."

At the pyramids in Cairo

At the pyramids in CairoReuniting at Home

Ardinst returned on the final plane carrying the released prisoners, only to encounter new challenges at home. “Unfortunately, Israel was not prepared. While citizens welcomed us warmly, the military police treated us with suspicion. Within 24 hours of our return, we were interrogated about our conduct in captivity, which made us feel unjustly accused. There was no real support system in place. Psychological assistance came only 25 years later, and in the early years we often faced dismissive attitudes.”

Since Simchat Torah 5784, have you found yourself thinking about the hostages in Gaza?

“Absolutely. Especially now, after so many have returned, I’ve spoken with several of the released hostages. While there are differences between our experiences, there are also striking similarities. Each situation is unique, but the core challenge is the same: the complete loss of control over your fate. Thankfully, today’s Israel responds very differently, surrounding returnees with support that simply did not exist in the past.”

Hope remains central to his outlook. “With most of the hostages now home, my thoughts are with those still missing and with the families who continue to wait. From my experience as a former captive, I know that survival is only the beginning, and that coping continues long afterward. I have deep faith in the strength and resilience of those who returned, and I pray for full healing, closure, and peace for all involved.”

עברית

עברית