Magazine

Faith Over Fear: Three Farmers Who Honor Shmita

They step away from their fields, their income, and their certainty every seven years. Through loss, challenge, and unexpected blessing, three farmers reveal what it truly means to live with faith.

- Tamar Schneider

- |Updated

Ira Zimmerman

Ira Zimmerman“Shmita is a mitzvah beyond human nature,” says Ira Zimmerman, a farmer from northern Israel, at the beginning of our conversation.

“For someone to abandon all their assets for an entire year, yet continue paying property taxes, maintenance, and other expenses?”

And yet, this is exactly what observant farmers do every seventh year: they stop working their land, relinquish ownership of their produce, and place their livelihood in faith. Each farmer has a different story, each struggles in their own way, but all share a deep, unshakable conviction. Sometimes they witness open blessing. At other times, only hardship lies ahead. Still, none are willing to abandon this mitzvah for any amount of money.

Three such individuals, Moshe Kahana, Eliyahu Shikutai, and Ira Zimmerman, share their journeys, their struggles, and what ultimately grows from the soil. Together, they offer a rare glimpse into quiet, modern Jewish heroism.

Generations of Shmita Observers

For Moshe Kahana, from Moshav Beit Hilkiah, observance was never a question.

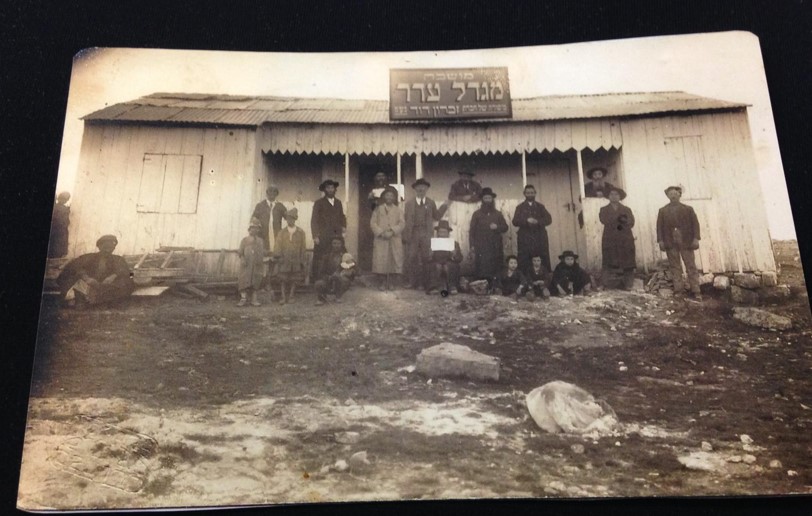

“My father and grandfather were farmers too, and they never relied on leniencies,” he says. “My grandfather was among the founders of Migdal Eder in 1920, which later became Kfar Etzion. Even in those harsh early years, they did not compromise. So for me, every seventh year I relinquish my fields and enter the study hall.”

Founders of Migdal Eder

Founders of Migdal EderHow do you manage financially?

“We have no organized financial plan, but that’s true every year. Farming is always a risk. Sometimes the fields yield almost nothing. From the outset, we hand our livelihood over to the Creator and ask Him to manage it. This profession is built on faith. The Gemara says that a farmer is one who ‘believes in the Living G-d and plants.’

“Even secular farmers from nearby communities ask me to pray for their crops. Once I told them to pray themselves, and they said no one ever taught them how. Yet you see how much their hearts long for blessing.”

But an entire year without income is different.

“After fifty years in agriculture, I truly don’t know how we managed to support a large family through multiple Shmita years. But we did. That is the miracle. Not dramatic stories, just the fact that we are still standing.

“If someone wants logic, they should understand that sometimes yields rise afterward. Ten percent more one year, thirty percent the next. Slowly, somehow, everything balances out.”

Kahana adds that agriculture in Israel itself defies logic.

“Much of this land is desert or heavy clay. Experts once claimed it could only sustain half a million people. Abroad, our soil would be used for pasture. Yet in almost every crop, we outperform countries with far richer land. That is Divine blessing. Everything here is spiritual, including the sabbatical year. You can see it clearly.”

Did you ever consider relying on halachic leniencies?

“As a young man in yeshiva, I learned with someone who later became a senior rabbi. He showed me writings attributed to Rav Kook stating that anyone with even a spark of fear of Heaven should avoid using such leniencies. Rav Kook established them out of compassion, not as an ideal. You cannot claim the covenant of the land and ignore its obligations.”

What about those who are not farmers?

“Support does not have to be financial. It can be moral and ideological. The Zohar calls those who observe this mitzvah ‘mighty heroes’ because they fulfill it not for an hour, not for a day, but for a full year. Someone who relinquishes livelihood for that long is a true hero. Those who observe this deserve encouragement.”

Faith Tested Through Loss

Eliyahu Shikutai, from Tzofar in the Arava, came to observance through hardship.

“Fourteen years ago, I rented seventy dunams of land in Jordan while also farming in Israel. That year, the temperature dropped to minus three degrees for three days. Every crop was destroyed. It was unprecedented. I saw clearly that only Hashem directs events, and how much this mitzvah tests our trust.”

Eliyahu Shikutai

Eliyahu ShikutaiThe year before, his yield had tripled.

“Instead of recognizing the blessing, I reinvested everything and lost it all.”

Even after observing the following Shmita, the challenges continued. A tomato crop he planted afterward collapsed when cheap produce flooded in from Gaza. Prices fell, and his entire harvest became worthless.

How did you face Hashem after such a blow?

“It left me with enormous debts and forced me to grow inwardly. I didn’t get angry. I asked what I was meant to learn. A neighbor who does not observe Shmita profited that year because he had insurance. I believe there are people Hashem speaks to through hardship, and others who are left untouched.”

Today, he no longer farms directly and will pause even his consulting work during the coming sabbatical year.

His wife Gili stands beside him fully.

“The many struggles around livelihood clarified for us how completely we are in Hashem’s hands. With our financial situation still difficult, we are preparing to observe the coming year too. After six years of constant strain, stopping is our only path.”

How do you manage practically?

“We receive support from Keren Hashviit and use what remains of our pension. We cut back where needed. We move forward with simple faith, believing this time is meant for rest, reflection, and Torah study, like an extended Shabbat.”

Gili explains that the inner growth has been profound.

“This fall took us from being givers to being those in need. It humbled us. We relied on family, and those bonds deepened. I remember sitting in the sukkah with all the siblings during a financially desperate year and realizing that the togetherness itself was the blessing.

“When we could no longer host others, we were left with just our family. That quiet forced us to confront ourselves and deepen our relationship. The hardship refocused us inward.”

Looking ahead, they remain firm.

“We thank Hashem that the struggle came in livelihood, not in health or children. We believe this path is shaping us. And we will not give up on this mitzvah.”

“Why Would I Give Up This Mitzvah?”

Ira Zimmerman grew up in a farming family near Gaza and became religious twenty-six years ago.

“As a child I knew nothing about the mitzvot tied to the land. Discovering them was a revelation. Today I farm vineyards near Or HaGanuz, harvest wheat, and work with olives. My entire life revolves around agriculture.”

Ira Zimmerman

Ira ZimmermanHis first Shmita, fourteen years ago, was terrifying.

“I wanted to keep the mitzvah fully, not symbolically. But I didn’t know how we would survive financially. I could have relied on leniencies, but I understood that today they are mostly economic tools. The real question was whether I believe Hashem provides.”

It was his wife who strengthened him most.

“We both left comfortable lives behind. I remember moving into a tiny yeshiva room with four students. After everything we had already given up, how could we give up on this?”

How did you manage that year?

“We lacked nothing. We saw clear providence. Keren Hashviit provided some support, not fixed, but enough to create a base. Beyond that, we saw guidance in ways that can’t be explained.”

He experienced encouragement even in the sixth year before.

“Normally I harvest around nine hundred kilograms per dunam. That year the harvest kept going. We needed more crates. In the end, we almost doubled the yield. I felt Hashem embracing me. I saw the same blessing among other farmers too. When someone commits to these mitzvot, they are not alone.”

Did you try to find other work?

“Even during Shmita, I still maintain the vines in permitted ways so we can return to work afterward. But the pace is different. I study far more and I am much more present at home. This will be our third sabbatical year. It’s still difficult, but now we understand the reality.”

How can the rest of us take part?

“Financial support matters deeply. When people share the burden, the farmer feels the entire nation stands with him. Some farmers can observe this mitzvah only because of that support. Without it, observance would be far more limited.”

Closing Reflection

Many still remember the uncertainty of the coronavirus period, when livelihoods vanished overnight and everyone longed for stability to return. Here are people who choose, willingly and repeatedly, to step into that uncertainty every seven years.

This devotion is never self-evident, especially in an era where most continue working as usual. Yet among silent fields, empty greenhouses, and resting tractors, true heroes continue to grow.

עברית

עברית