Magazine

"You Were Chosen”: The Fathers of the Kidnapped Teens on Grief, Faith, and Unity

Private pain, public mission, and the unity that briefly changed Israel

- Hidabroot

- |Updated

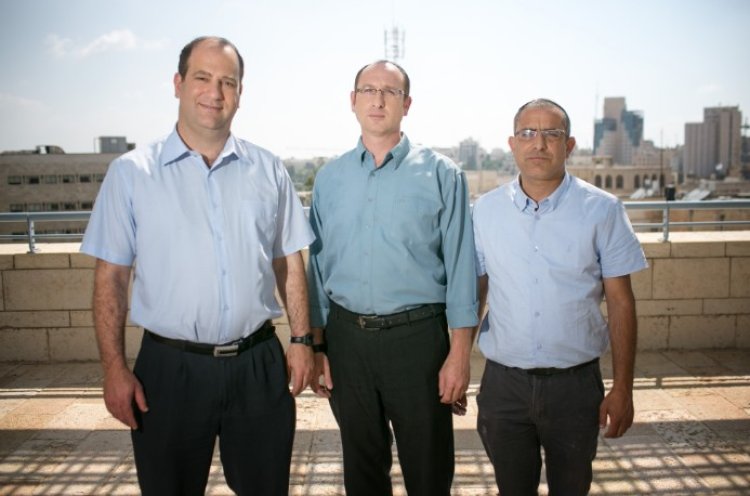

Photo by Noam Moskowitz

Photo by Noam Moskowitz“I don’t even remember what time we went to sleep,” begins Uri Yifrach, father of Eyal (of blessed memory), in a quiet, heartbreaking monologue. “The days weren’t really days, and the nights began close to morning. The house was full of people all the time. Someone stood at the entrance to keep random strangers from coming in — but still, there was an endless stream of visitors you couldn’t really turn away. I’m an introvert; I wasn’t used to that. Suddenly there was all this chaos around me, all the noise. And then when night came and the house finally emptied out, suddenly it was quiet.

“I remember those hours. You sit there and fold into yourself, shrinking inward, while your thoughts race ahead. The silence you longed for all day suddenly feels so threatening. Specifically in those silent hours, I wanted someone to burst in, bang on the window, break into the bedroom — tell me they found him, that everything was okay. That was my fantasy for those weeks: that someone would wake me up in the middle of the night, not just knock politely at the door, but come suddenly, in surprise, and tell me they found Eyal and everything was fine. That’s all I thought about.”

A year has passed since the events of that summer — events that left a deep imprint on everyone who lives between the sea and the Jordan. No Israeli can forget that war. The elections that followed were only a distant echo. It was the summer that united Israeli society: the bloody operation in Gaza, the tunnels, and so much more. But before all else, it was the summer when three teenagers were abducted and murdered — Eyal, Naftali, and Gilad (of blessed memory).

For the fathers — Uri, Avi, and Ofir, that summer is present every morning, every day. “It can be a family event and I find myself scanning the room, looking for Naftali,” says Avi Frenkel. “On vacation I think of asking him to help, I remember how I used to explain things to him — and then I remember again. Memory has no schedule; it comes and goes. Every single day it’s there. It’s constant pain, burned in.”

Over the past year, it was the three bereaved mothers who stood at the front of the media. The fathers stepped back and gave them the stage. The world heard the mothers’ pain — and much less from the fathers beside them. Not by accident. When I speak with them, the emotion is more restrained. Memory sits on their faces, present in every movement. They speak sparingly, as if guarding their sons’ memory inside their hearts — private, protected. They struggle to talk and expose too much, afraid of losing their sons all over again.

![Photos: Noam Moskowitz]() Photos: Noam Moskowitz

Photos: Noam Moskowitz

Photos: Noam Moskowitz

Photos: Noam MoskowitzNo Day of Forgetting

I meet the three fathers in Jerusalem, near City Hall. Just an hour earlier they had left the office of Mayor Nir Barkat, where the Unity Prize they initiated together had officially been launched. As we talk, they move back and forth between the bitter grief that has become their daily reality from that rushed Friday — and the public work that now fills them, offering meaning, perhaps, to the searing memory that will not let go.

“This is a bitter tragedy,” Uri Yifrach says. I ask him when he remembers his son, and he lifts his eyes to mine. It is hard to meet his gaze. Yet his eyes remain steady. It matters to him to raise Eyal’s memory — this is not random. He keeps speaking because he has a purpose.

“I think about Eyal every day. In every place and every action he’s present. I never know what will suddenly flood me with memory and make me break down crying. Just yesterday morning I got a message from a group Eyal helped establish when he was in 12th grade. They named it after him — Garin Eyal, and yesterday they brought in a Torah scroll. Someone wrote about it and sent me the article.

“I read the message and a curtain of tears covers my eyes. Suddenly Eyal’s memory is alive and standing right in front of me — active, energetic, always running, never standing still. I remember when he went there in 12th grade and I asked him, ‘Eyal, what’s so urgent? Why not learn another year in yeshiva and go afterward?’ I think about that and I can’t breathe. It shatters you into pieces — just like that, in an instant.”

Uri continues, tears sliding down his face as he speaks about other thoughts. “I remember how much he cared about the Jewish people, about doing, about building. And I know that what we’re doing now — this work for unity in the Jewish people, is exactly what he would have done. I know it. I remember my child. I know what was always on his mind.

“I think about his final moments there — in the killers’ car, and I know he thought about the Jewish people. I’m sure that if he resisted, it was because he was thinking about our fate, our purpose. That was Eyal. That was always him. And I hope what I’m doing now is what he would have done. I’m sure he’s happy about it.”

What can you even ask a bereaved father? I sit with that question, heavy in my chest, facing three fathers — three men who became symbols for an entire nation. The unity that gathered Israeli society around them was rare in a tribal, fractured landscape. The three men in front of me, in the most tragic circumstances, became the face — and the heroes, of that unity.

“You Were Chosen”

“By Friday we were already being updated on the details,” Uri Yifrach says. “The abduction, the prayers — everything organized within hours. On Sunday morning my father came to me. I remember him standing in the doorway. My father is a man of Hebron. I was born in Kiryat Arba. He looked at me in pain and said, ‘Uri, you were chosen.’ Chosen for what? I asked him — though I already knew the answer.

‘What is happening here among the Jewish people is something immense,’ he told me, ‘and you were chosen from Heaven.’ Did I want this choice? Absolutely not. I’m quiet. Introverted. Not a public person. But from Heaven they chose me and my family for this mission, and I accept the decree with love.”

Uri describes how, during the shiva, then–Education Minister Shai Piron called and asked to bring a delegation of Tel Aviv school principals to Uri’s home in Elad. They came; they sat; they talked. “At the end one of the principals approached me and said, ‘Mr. Yifrach, I want to bless you with one thing — may it be God’s will that you return to being an anonymous family.’ He said it, and I knew, I felt, that it was the only thing I truly wanted — that all of this would vanish, dissolve, that they would find Eyal and everything would go back to normal, that the quiet would return. But it didn’t happen.”

Instead of quiet, the families received the full spotlight of Israel. Despite their efforts, their homes became centers of prayer and pilgrimage. From the outside it looked as if families living through unbearable uncertainty never had a moment to themselves. In a broad sense, they became a public “possession.” I ask about that invasion of privacy — the way public life entered their living rooms.

“I didn’t like it, and it wasn’t easy,” says Ofir Sha’ar. “But I understood the need that came from the people. There was extraordinary unity. They wrapped us in warmth like nothing I’ve ever seen. You couldn’t not take part in it, even if it came at a personal cost. But the cost was heavy, deeply personal. Because beyond the memorials, the gatherings, the rallies — there is the private pain, the inner pain, that accompanies every moment of my life. This is bereavement, and it’s daily.”

Avi Frenkel also didn’t seek the exposure. “We’re not people for whom publicity was a goal. The opposite — I personally struggle with it. The goal was to carry a message, to try to continue what we felt then.” Uri says the same: “All we wanted was that something strengthening would come out of it. That’s what matters to us. The exposure is not easy. It comes at the expense of your personal emotions and the desire to mourn privately. But after all the love and support that the people poured on us — you can’t not give something back.”

Professional, and Human

Everyone remembers the sequence: the rumors, one after another. Friday afternoon came the terrible news of three teens forced into a car at a junction in Gush Etzion. Later the car was found burned. On Saturday night, senior army officials were already in the families’ homes. It didn’t look good. But the message was: it’s still possible they’re alive.

The next three weeks blended into one long block of fear. A few days later the recording was released — Gilad Sha’ar calling the police, reporting he was being abducted. Then the famous shouts: “Heads down,” the heavy accent. Hearts across the country shook, while the dispatcher failed to grasp what was happening.

Later came the bloodstained glasses and other evidence that eventually led to the discovery of the bodies, and the understanding that the worst had happened. This was not an abduction for bargaining. The boys were murdered almost immediately after being taken into the car.

When I ask when they understood their sons were not alive, they say that until the bodies were found, hope still pulsed inside them. “The day before the bodies were found, there was a massive unity rally in Rabin Square,” Uri Yifrach says. “A unity gathering of every sector of the people like we’d never seen. I told myself: with unity like this — if tomorrow they find Eyal alive, it will be unbelievable. The next day they did find him — his body.”

Do they feel anger at the police? At the handling? The answer is no. All three repeat it. Perhaps some things could have been done differently, but overall they stand behind the security system.

“When they first brought me the recording to hear, I hesitated — could I even listen?” Uri says. “We already knew it existed from Saturday night. The media also knew, despite the gag order, because they feared endangering them. I listened five or six times with headphones, again and again.” In the recording, Gilad can be heard; Eyal is not heard at all.

“I had so many questions. You couldn’t understand anything. Even today, when we more or less know what happened, we can only guess. But then, everything was open. I hardly understood what I heard. Were those real gunshots? Were they murdered? And why don’t we hear Eyal? It threw me into a storm. I told my wife not to listen, that it would be too hard for her. And she didn’t. It wasn’t simple.”

Did the recording make you think about Eyal’s final moments?

“Yes. Later I understood it’s very possible Eyal was already not alive during that call, that the boys were murdered during the drive. I thought about Eyal in the car, understanding what was happening. He was smart, quick to react. It’s not easy to think about your child in such a situation. But I think I know what occupied him then. I think what I’m doing now is the path he would have wanted.”

Uri also explains the police reality. “Of course a faster response would have been better. But in the end, about 45% of calls that come into Jerusalem police are false reports. It’s not that someone listened and thought: an abduction? Whatever, let’s get coffee. And remember, the recording was published after noise was cleaned up — in far better conditions than what existed in real time.”

Avi Frenkel adds the harsh bottom line: “Even if the police had reacted instantly and sent Yamam to the scene, we now know it wouldn’t have changed the outcome. Maybe it would have saved weeks of searching and uncertainty. But it wouldn’t have prevented the murder. Tragically, the murder happened along the way.”

They apply the same approach to the army representatives who updated them. Looking back, it was more murder than abduction, and some felt the army wanted to frame it as an “abduction” for reasons not purely practical. The families reject that. Throughout, they say, army leaders were honest about the odds and about the efforts underway. “We were able to try to sleep,” they say, “knowing the best of Israel’s soldiers were doing everything possible to bring our children home.”

The Prayers Helped the Jewish People

The difficult weeks passed, and then the bitter news arrived: the bodies were found. Hope ended. Naftali, Eyal, and Gilad would never come home. Even now, the fathers don’t speak much about those exact moments. Unlike their wives, who find strength to describe and reconstruct, the fathers wrap themselves in silence, in the pain of memory.

Uri Yifrach still wants to say something — a message like an arrow aimed at the heart of anyone who remembers those fateful days. “I know,” he says, “that we all see those days as hard days, a hard hour. But personally, I don’t see it that way. In my eyes, those were days of elevation and spiritual rising.

“The hardest moments — finding the bodies, the funerals, the endless crying, the memories that wrapped around us — of course all of that was there. But behind it was a sense of uplift. This people can create brotherhood and agreement. After some time someone from our community in Elad told me those days were like Yom Kippur for him — 18 days of Yom Kippur. Prayers, Torah, repentance. With all the pain, we must not forget that.”

The ability to rise from the private world of the father into something larger is what defines these parents. “Every day I tell myself,” Ofir Sha’ar confesses, “you’re not only Gilad’s father — you’re also the father of five daughters. You’re in a role. You can’t collapse.” And they don’t collapse. They carry an entire nation on their shoulders — one whose heart shattered watching those scenes. Without the strength of those families, who knows if the pieces could have been stitched at all.

The bodies were found, and within days Israel was swept into war. The murder of the Arab teen Muhammad Abu Khdeir in Jerusalem ignited riots. In the south, war erupted. The IDF understood the looming danger: the tunnels. It was forced into a ground operation in Gaza. “Bring Back Our Boys” ended in quiet, and Operation Protective Edge surged forward. Yet the unity seen in the eyes of thousands at the funerals continued into the war.

Avi Frenkel believes the chain is inseparable. “Anyone who understands what happened knows it. It was a direct, unequivocal result. The unity of Protective Edge came after the unity around our tragedy — an illumination from Heaven.”

Uri takes it further. “People came to me and asked: what about all the prayers? Where did all those hours of crying out to God go? That is a hard question. We don’t know the ways of Heaven. We went to great Hasidic rebbes and rabbis, and all promised they would pray and do everything they could. Teachers in the cheder in Elad told me their students asked: where did the prayers go?”

Then Uri answers — not only as a question, but as faith that warms even as it burns. “Think what disaster was prevented for the Jewish people that summer. Think about the tunnels reaching into the heart of the country. If the IDF hadn’t reached that war, if the operation that began immediately after the bodies were found hadn’t happened and the south had stayed quiet — there could have been a catastrophe on a far larger scale. Terrorists infiltrating through those tunnels could have carried out an attack that paralyzed Israel.

“I am certain those prayers — the tens of thousands of chapters of Psalms, cries that rose to Heaven, stood as merit for the Jewish people. Our children could no longer be saved,” he says, his voice breaking. “They were already murdered by the time we learned what had happened. But those prayers went and acted on behalf of the entire people of Israel, and you can’t not see it clearly.”

These words of faith, spoken softly, carve into the heart, directly, simply, and impossible to dismiss. Comfort spoken from the depths of a father’s broken soul.

We Will Keep Working for Unity

Three months after the abduction, the kidnappers and murderers were eliminated. Shin Bet located them in a basement of a carpentry shop in Hebron. Yamam fighters surrounded the building. When the suspects refused to surrender, an IDF bulldozer opened a hole in the basement ceiling. The terrorists opened fire; the fighters responded with rifles and grenades. The killers were killed.

I ask if the parents felt relief or closure.

“They were creatures who didn’t deserve to live, and it’s good they died,” Avi Frenkel says. “But comfort? There is none. How can there be comfort? There was satisfaction that they died, but I didn’t feel closure. Not at all.”

Uri also rejects the idea. “Closure? Absolutely not. They were cursed hunters who hunted my child. That’s how it feels — human hunters, animals. So one hunter was caught — what comfort is that? What does it have to do with my child who died? It doesn’t. What is justice in a case like this?”

If there is any comfort, they find it in shared action — by turning unity into something ongoing.

How did the idea of unity begin?

“Jerusalem’s mayor, Nir Barkat, was the first to raise it,” Ofir Sha’ar says. “He visited each family at home and suggested taking the unity in the Jewish people one step further. He proposed founding a Unity Prize to be awarded to an individual or organization active in building unity. We connected to it deeply. Later he reached out, and it began to roll.”

Uri and Avi tell the same story: Barkat saw the rare unity surrounding the families and wanted to carry it forward. He suggested it; they joined. There was no way not to. The circumstances were unimaginably tragic, but it was a rare hour of national togetherness. Later they created unity dialogue, launched a public campaign calling for a Unity Day on the anniversary of the boys’ murder, and facilitated meetings between political and social extremes in Israeli society.

I ask Avi Frenkel whether he truly believes unity is possible. After all, it’s clear that much of the unity came from solidarity with the families. The fractures in Israeli society run deeper than any campaign. Frenkel doesn’t trade in illusions: “Will we solve the conflict in Israeli society? I don’t think we have that kind of power. But we can absolutely reduce it. Remind people that another way is possible.”

He tells a parable: a man walking in darkness, in a place full of potholes and obstacles. Suddenly a bolt of lightning flashes and illuminates the path ahead — then disappears, and the darkness returns, even worse than before. “But at least now the man has the memory, the knowledge of where the obstacles are. He knows where not to step.

“Those weeks last summer were that flash of light. And our goal is to bring it back, and to restore that memory of the lightning. To remember that another way is possible. Protective Edge showed that this is also a security interest of the highest order.”

Evening sounds settle in, and the three fathers begin to part. The past year has strengthened the bond between the families, turning them into one large family. The bitter memory, reflected in their heavy eyes, breaking through their silence and even through the forced smile at the corners of their mouths, has drawn them close.

They shake hands warmly and promise to speak again, each turning to his car and to his private world, where bereavement reigns, and pain is sharp. Only the public work, one of them tells me, compensates a little — loosens the grip, for a few moments, of the memory that never leaves.

“My wife still sends him messages,” he says. “She writes to him, this happened, that happened — she writes him letters, tries to speak to him and tell him what has changed, what’s happening in the world. But at the top it always says: ‘Last seen 12/06/2014.’ It doesn’t change. Our son is gone.”

And the grandfather’s words echo in the air: You were chosen.

עברית

עברית