Magazine

Raising Yair: A Father’s Journey of Love, Determination, and Life with Down Syndrome

From hospital battles to a historic moment on stage with the Shalva Band, David Fumberg shares how unconditional love, persistence, and faith shaped his son’s independent and joyful life

- Moriah Luz

- |Updated

David Fomberg and his son Yair

David Fomberg and his son YairWhen David Fumberg sat in front of the screen and watched his son Yair on stage in the United States, nothing could have prepared him for what was about to happen. In truth, nothing about that moment was self-evident. Yair, who has Down syndrome, was playing the drums as part of the Shalva Band, a group made up of children with special needs. The band had been invited to perform before President Donald Trump himself.

“The band’s musical director received a very clear instruction from the security forces there: no one was even to think about approaching Trump,” Fumberg recalls. When the music ended, the musical director made a bold decision. He leaned toward Yair and whispered something in his ear. “You don’t need to tell Yair something twice,” Fumberg says with a smile. “He ran straight over and gave Trump a big hug, and then the rest of the band followed. Once it started, no one could stop it.”

The musical director was reprimanded afterward, but the historic moment remains unforgettable.

“I’m the father, and he’s my son”

Fumberg, 67, is married to Shifra and is the father of five. He lives on the religious kibbutz of Hafetz Chaim. One month before Yair, their fourth child, was born, routine tests revealed abnormal findings. “They couldn’t tell us exactly what the problem was,” he says. “We just knew that something wasn’t right.”

Immediately after the birth, the newborn was taken for tests, which confirmed the diagnosis: a chromosomal condition, Down syndrome. “The first thing I said was that I’m his father, he’s my son, and that’s the end of the story. We’re going to raise him like any other child, as much as possible. At the time, I had no knowledge whatsoever in this field.”

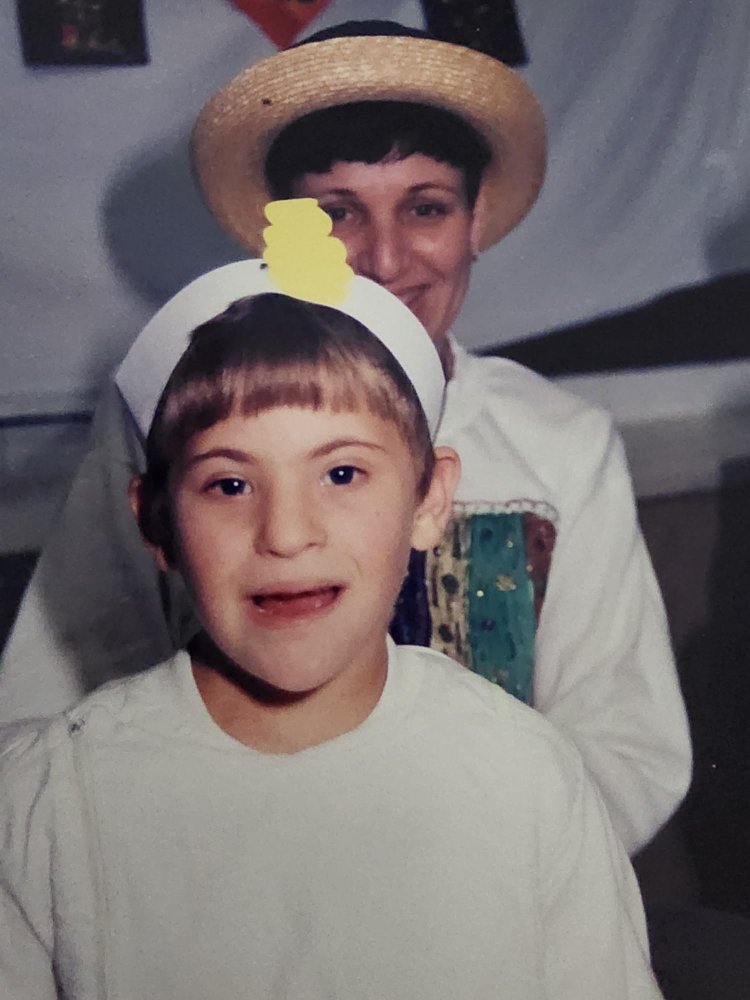

Yair's birthday

Yair's birthday

Yair was born with an intestinal blockage, and at four days old he was rushed by ambulance to Hadassah Ein Kerem Hospital for surgery. “I have a photo of him connected to countless tubes and wires,” Fumberg recalls. Every day he traveled from the kibbutz to Jerusalem to be by his son’s side. “I couldn’t do anything, but I was there from morning until night.”

After about a week, Yair was released home, on the condition that Fumberg return immediately to the hospital for even the slightest medical concern. “And then,” he says, “we started World War Three.”

“Israel was different back then”

“Israel thirty-seven years ago was very different from today, in every sense,” Fumberg explains. “As far as Yair was concerned, I didn’t see anyone else. Everything I understood, learned, or believed would be good for him was done.”

Was it something you kept hidden from the community?

“Not for a second,” he answers. “When I went to tell my parents, they were terrified. In those days, people didn’t talk about things like this, and many children with Down syndrome were literally hidden away.” He remembers how hurt he was when neighbors avoided congratulating him on the birth. “They didn’t know how to approach me,” he says.

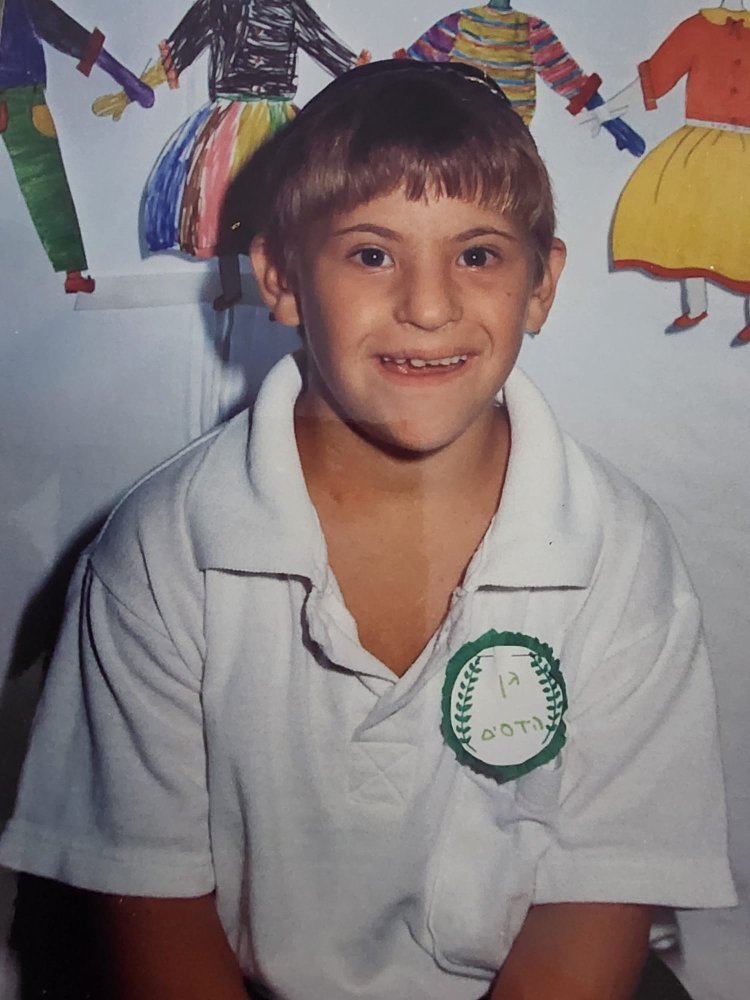

Yair in preschool

Yair in preschool

A phone call from the Prime Minister’s Office

The first time Fumberg had to develop thick skin on behalf of his son came quickly. When Yair was only a few weeks old, he was scheduled to begin occupational therapy due to low muscle tone. Upon arriving at the hospital, Fumberg was told there was no room and that Yair could not begin treatment. “I told her, ‘I understand. Thank you very much. He starts tomorrow.’ And that’s exactly what happened.”

Until fifth grade, Yair studied in a regular school. On the eve of fourth grade, Fumberg received a call from the principal, who told him bluntly that there was no point in bringing Yair to school the next day. A government decision had canceled funding for aides, and without an aide, Yair could not remain in the classroom.

Cell phones were rare at the time. Fumberg sat down at a fax machine and sent messages to everyone who mattered, “with very clear language that this would not work for me.” The school year began, and Yair stayed home. Two days later, Fumberg received a phone call from the Prime Minister’s Office. The current president, Isaac Herzog, was then the director general of the office. “He called me in the middle of the day and asked, ‘What’s going on? I’m getting calls from all directions.’ I told him, ‘I have a child with Down syndrome. You took away his aide. That’s unacceptable. He’s sitting at home.’ The next day, he had an aide.”

“This was born with Yair”

“Was I always like this?” Fumberg asks rhetorically. “No. This was born with Yair. In no other area of my life do I behave this way. But when you have a helpless child who cannot take care of himself, you have no choice. And it never really ends. My wife once described it beautifully: it’s like the sea. One wave comes, one wave goes, and another one is already on its way.”

Yair was, in his words, “a daddy’s boy.” “My wife raised four children, and I raised him,” he says with a smile. “I did everything with him.” Three times a week he drove Yair to therapies: occupational therapy, speech therapy, drumming lessons, swimming, whatever was needed at each stage.

Living on a kibbutz far from treatment centers required enormous effort. At the time, the kibbutz operated with a shared economy, and private cars were not allowed. Vehicles were allocated according to need and schedule. “Yair’s appointments were precise. If we missed a slot, that was it, we could go home.”

When delays began to cost Yair appointments, Fumberg implemented what he calls “Plan B.” He took taxis, saved the receipts, wrote explanations on them, and submitted them to the kibbutz administration for reimbursement. “Very quickly, cars started showing up on time again.”

Growing into independence

In sixth grade, Yair transferred to Nitzanim School in Jerusalem, a school for children with special needs. At seventeen, he joined the Shalva Center, which became his second home. When he turned twenty-one, he was supposed to leave, but the musical director of the Shalva Band, Shai Ben Shushan, promised to make sure Yair stayed. Today, Yair works at the café there, plays drums in the band, and comes home to his parents once every three weeks for Shabbat.

Fumberg emphasizes Yair’s independence. “Very early on we understood that for him to be happy, and for us to be okay, he needed to be as independent as possible. Anything we could do to make that happen, we did. Today he takes the bus on his own, works, earns money, lives in supported community housing, and thrives.”

Yair at the cafe where he works

Yair at the cafe where he works

What best defines Yair?

“Unconditional love,” Fumberg answers without hesitation. “He smiles, hugs, and is always happy to help. Not long ago, he told me he helped a woman with a stroller get it onto the bus.”

Despite Yair’s maturity, parental guidance is always needed. “Yair will always be a child,” Fumberg says honestly. “But we keep trying, all the time, to improve things as much as possible.”

Yair with neighbors from the kibbutz who came to visit the cafe

Yair with neighbors from the kibbutz who came to visit the cafe

Toward the end of the conversation, Fumberg is asked a difficult question: was there ever a sense of a shattered dream when Yair was born?

“I don’t think about it,” he answers simply. “What would that give me? Would it turn him into a different child? This is what God wanted, and I accepted it with love. I did what needed to be done, and I keep doing it, without thinking twice. It’s not even a question.”

עברית

עברית