Magazine

From Foreign Worker’s Son to Jewish Soul: Howie Yosef Danao’s Journey of Identity, Faith, and Music

Born to a Filipino mother, raised in Tel Aviv, and drawn to Judaism through struggle and song, Howie Yosef Danao shares a powerful story of conversion, belonging, and spiritual purpose

- Moriah Luz

- |Updated

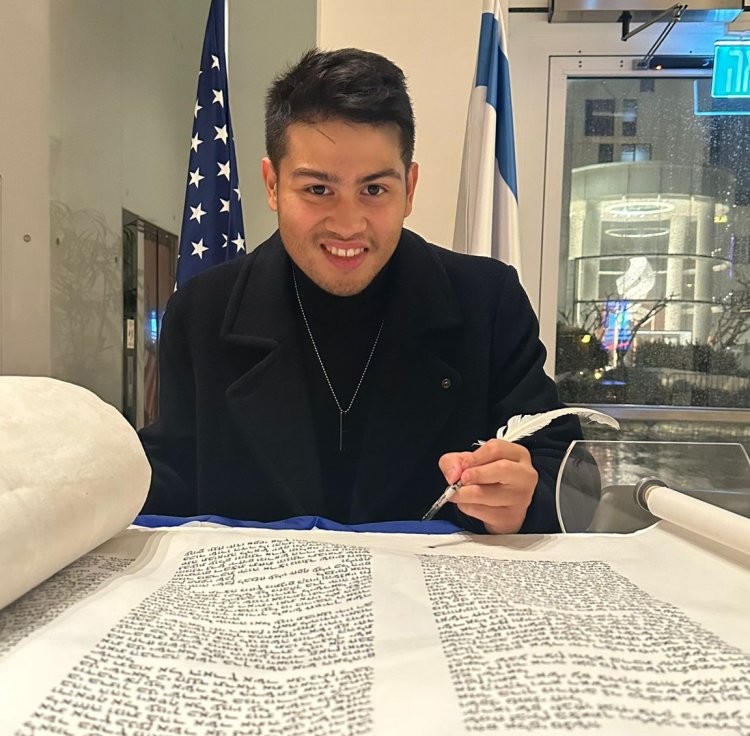

Yossi Danao (Photo: Elchanan Kottler)

Yossi Danao (Photo: Elchanan Kottler)As we begin our conversation, Howie Yosef Danao receives a phone call and gently apologizes. On the line is his mother, a Christian Filipina from Tel Aviv. The gap between the soft spoken yeshiva student and the journey of his life is almost impossible to grasp. Howie’s extraordinary story begins nine months before he was born.

His mother divorced his father, left the Philippines, and came to Israel as a foreign worker. A well off family from northern Tel Aviv hired her as a housekeeper, and her future seemed secure.

A few days after she began working, she started experiencing unfamiliar pains. A brief medical check revealed a surprise that would change her life. She was pregnant. Her first thought was to return to the Philippines, where her family lived. When she informed her employers, they refused to hear of it. Although they had known her only briefly, they were unwilling to let her leave. They told her that she and her unborn child would become permanent members of their household. And so it was. Howie was born into this unusual reality.

“I Won the Lottery Without Buying a Ticket”

Howie, now 25, or Howie Yosef as he has been called for the past three years, was married about a month ago to a woman from a religious family in Samaria. The couple lives in Ramat Gan, near the yeshiva where Howie studies in the mornings. He is a singer and also gives lectures in Israel and abroad under the title “Love and Faith,” in which he shares his highly unconventional life story and strengthens Jews in their faith.

“I grew up with my biological mother and with an additional set of adoptive parents,” he begins. “They treated all of us as one family in every sense. I would come home from school and my Israeli ‘sister’ would naturally make me a hamburger or pasta.” His adoptive parents gave each of their children their own floor in the house, and Howie and his mother were given a floor of their own. “They showed us incredible kindness,” he emphasizes.

Did you ever feel second class in any way?

“Only outside the house. Inside, everything felt completely normal and family like. But once you stepped outside, it wasn’t taken for granted. Even visually, I stood out. I was the only Filipino child in my class.”

For years, Howie struggled with guilt. “I grew up in northern Tel Aviv, with a very comfortable economic reality. My mother had Filipino friends in Israel, and through them I met Filipino children my age. At every such meeting, it was obvious that my lifestyle and standard of living were completely different from theirs. I felt as if I had won the lottery, even though I never bought a ticket.”

Howie grew up as a quiet, introverted child. “I had one real friend, a neighbor who was in my class.” Music, which accompanies him to this day, became his entire world and a source of comfort and encouragement. “In third grade, I started writing, composing, and playing guitar. I no longer needed time to play with friends, because my free time was filled with music.”

Would you say music was your escape?

“Yes. It was my life. Without music, I probably wouldn’t be alive. Today I would answer differently,” he immediately clarifies. “I realized that if music is life, then what happens when there is no music? What holds you up and gives you meaning? And indeed, in those years, when I wasn’t involved in music, I fell into deep depression and very dark places.”

Music proved not only to be a source of meaning, but also one of his strongest talents. At 18, he participated in a well known competition for emerging musical stars and advanced far. Then, at what felt like the peak of his success, something changed everything. Howie was drafted into the army. “Suddenly I couldn’t focus on music, and everything I had repressed came flooding up.”

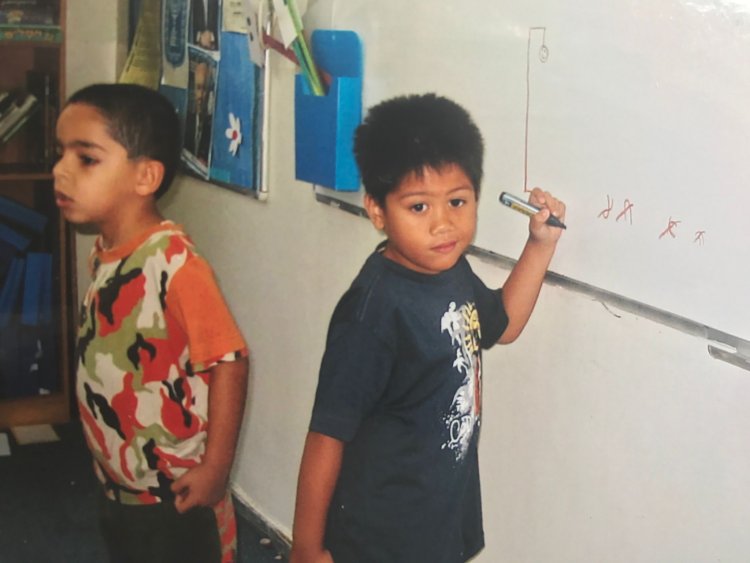

Howie at school

Howie at school

What had you repressed?

“From a young age, an identity crisis was brewing inside me. I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere. In the army, that feeling intensified. If you asked my friends why they enlisted, they would say, ‘For the Jewish people,’ or ‘Because I’m Israeli.’ Those answers weren’t true for me.”

“So Many Stereotypes Shattered”

A few months before his discharge, while serving in a human resources role in the Air Force, Howie heard about the Nativ program. “It’s a course for non Jewish soldiers in the IDF, designed to help them find their Israeli identity,” he explains. The program included weekly tours around the country, and through it he was exposed to a broader and unfamiliar picture of the Jewish people.

“For the first time, I was surrounded by people like me, who felt the same things I did. I felt we were all on the same boat, just not sure where it was sailing,” he laughs. He shares that his adoptive parents were wonderful, kind people, but completely disconnected from Judaism. “They lived like people abroad, without anything tying them specifically to where they were.”

“As I studied, many stereotypes shattered. I discovered that Judaism is a complete way of life, not just a set of rules.” One of his first insights concerned the guilt he felt over his socioeconomic fortune. “I understood that someone chose for me to be born in the Land of Israel. Neither I, my mother, nor my adoptive family had any control over that. Someone chose me to be here. I could have fought that realization my whole life, but instead I chose to choose back the One who chose me. I chose the Creator and the people He chose.”

Howie began a long conversion process that lasted about three years, far longer than usual. During that time, he stood twice before a rabbinical court that refused to convert him. But he did not give up. “I won’t say I didn’t cry. There was sadness. But quitting was never an option.” The third time, the judges informed him that his conversion had been accepted. “They told me, ‘We are approving you because we look into your eyes and see a Jew.’”

How did you feel when you were accepted into the Jewish people?

“Throughout the process, I said that if I converted, I would have succeeded in life. The feeling was so intense that I was convinced that the moment I emerged from the conversion immersion, God would decide to take me from this world, because my soul had fulfilled its mission.”

That sense of having reached the peak of his life stayed with him for a long time. Only when he met his wife through matchmaking did something in that outlook change. “My wife taught me that my purpose isn’t to die as a Jew, but to live as a Jew.” His mother and adoptive parents were present at the wedding. “I call it the ‘wedding of redemption.’ There was an extraordinary unity among the parents, the families, everyone.”

“If I’m a Singer, I Have Responsibility”

One of the first areas where his transformation became evident after deciding to convert was music. “A childhood friend who used to make music with me came over. He heard me play and blurted out, ‘Who are you?’ He didn’t recognize me at all. Music is my form of expression. The more I connected to myself and my identity, the clearer my expression became.”

Today, he sees his music as a mission. “If I create, my responsibility is to guard my intentions and be conscious of them. That’s why after my conversion I began to be careful about women’s singing. This is a spiritual profession, and I need to be aware of spiritual forces and order.”

Another area he now views differently is the racist remarks directed at him because of his appearance. “They started when I was a child and continue to this day, through nicknames, direct rudeness, or even so called positive discrimination,” he laughs, recounting how a schoolteacher once slipped him a bag of used clothes at the end of the day, which he didn’t need at all.

“For me, there’s a fundamental difference between the racism of the past and that of today. After I converted, someone who calls me names isn’t just a random person. He’s my brother,” he says, without a trace of cynicism or resentment.

When you hear those comments today, don’t you feel anger, or question why you went through such a difficult process?

“No. On the contrary. If I didn’t encounter such reactions, I wouldn’t have the opportunity to connect with another Jew. That’s my most direct channel to reach him.” He shares an incident in which a stranger on the street called him a monkey. “He said that because he had no other way to react to what he saw. Just as I grew up in northern Tel Aviv, where my perception of Judaism was shaped in a distorted way by the media consumed at home. When another Jew sees me and reacts negatively before knowing me, it’s only because he doesn’t know another way to define me. In my eyes, that’s why God brought us together.”

“Today I even say that other people’s racism is my livelihood,” he smiles. “Our role, and what I try to do in my life, is to step back from that discourse and bring hearts closer. Maybe it’s too idealistic or even sounds naïve, but just as we hope for Mashiach to come today and for the Temple to be rebuilt, we also need to try to treat one another as Jews.”

עברית

עברית