Parashat Mishpatim

Between God and Man: Why Jewish Law Is Built on Compassion

How Parashat Mishpatim reveals that faith in God is inseparable from sensitivity to others

- Rabbi Reuven Elbaz

- |Updated

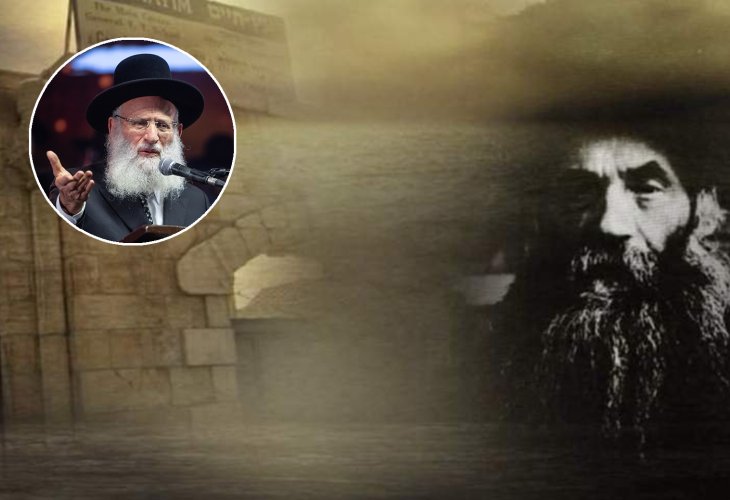

Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer (screenshot)

Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer (screenshot)“These are the laws that you shall place before them” (Shemot 21:1).

Rashi explains: “Whenever it says ‘these,’ it disqualifies what came before; whenever it says ‘and these,’ it adds to what came before. Just as the earlier ones were given at Sinai, so too these were given at Sinai.” Some explain that in the previous portion, Yitro, the Torah focused more on matters between man and God, the preparation and sanctification before the giving of the Torah, whereas this portion focuses primarily on commandments between one person and another.

In truth, even within the Ten Commandments themselves we find both categories of commandments between man and God and commandments between people. The Sages say (Kiddushin 31a): “What is the meaning of the verse, ‘All the kings of the earth will thank You, O God, for they have heard the words of Your mouth’? It does not say ‘the word of Your mouth,’ but ‘the words of Your mouth.’ When the Holy One, blessed be He, said ‘I am’ and ‘You shall have no other gods,’ the nations of the world said: He is demanding this for His own honor. But when He said, ‘Honor your father and your mother,’ they returned and acknowledged the truth of the earlier statements.”

Rava explains further: “From here we learn, ‘The beginning of Your word is truth.’ Is it only the beginning and not the end? Rather, from the end of Your word it is evident that the beginning is truth.”

The later commandments dealing with relationships between people, are what gave strength to the earlier ones. Through them, the nations of the world understood that God was not acting for His own sake, but for the good of humanity. Without faith in the Creator, people would not uphold even interpersonal laws, because one who has no God has no Judge and no accountability. Such a person can do whatever he pleases. Yet when even the nations behold commandments about honoring parents, respecting others, and the system of laws that protect society, they understand that God truly seeks the good of the world and its continued existence.

We, the children of Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov, believers descended from believers, do not need to defend God. We know that even the commandments dealing with faith in God were given for our benefit. What a blessed life a Jew lives when he lives with faith, entrusting himself to God, knowing that God sustains him and provides all his needs. For us, faith is the foundation of human existence and of the world itself.

The True Rehabilitation of a Thief

The portion opens with the laws of the Hebrew servant. It is striking to see how the Torah relates to him, to the point that it is hard to believe we are dealing with a lowly thief who was caught and had no means to repay what he stole, and whom the court therefore sold so that he could earn money and repay his debt. The Torah commands the master who acquires him to care not only for the servant himself, but also for his wife and children, and to support them as well.

The Sages derive from the verse “for it is good for him with you” (Devarim 15:16): “With you in food and with you in drink, so that you do not eat fine bread while he eats coarse bread, you drink aged wine while he drinks new wine, you sleep on soft bedding while he sleeps on straw. From here they said: whoever acquires a Hebrew servant is like one who acquires a master for himself.” Tosafists add in the name of the Jerusalem Talmud that sometimes there is only one pillow. If the master sleeps on it himself, he does not fulfill ‘for it is good for him with you,’ and if he neither sleeps on it nor gives it to the servant, that is the trait of Sodom. Therefore, he must give it to the servant and become, in effect, a servant to his servant.

Through such treatment, the servant can rehabilitate himself and begin to build a new life of consideration for others, responsibility, and care. He will no longer extend his hand to steal.

What does God gain from this? Nothing at all. This is clear testimony that the Torah was given for the benefit of humanity and the world, not, Heaven forbid, for God’s own honor. Thus the portion continues with many commandments between people, all sharing one theme of care for others, sensitivity to their feelings and needs, and refraining from causing harm.

Would I Cause Her to Stop Singing?

Rabbi Elazar Menachem Man Shach once related that in his youth he would accompany his uncle, the great Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, author of Even HaEzel, who later immigrated to the Land of Israel and served as head of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in Jerusalem. The purpose of these walks was to learn from his uncle’s conduct and ways. Naturally, during their walks they never spoke mundane matters, but engaged in Torah, fulfilling “You shall speak of them… when you walk on the way.”

One day, Rabbi Shach accompanied Rabbi Isser Zalman to his home and noticed that he entered the house, then came back out moments later. After waiting a few minutes, he tried again, but once more came out quickly. Seeing Rabbi Shach’s surprise, Rabbi Isser Zalman explained: “My wife employs a widowed woman as a house helper so that she may earn a small livelihood. When I entered the house, I heard the widow singing behind the door. I hurried to leave because of the prohibition of listening to a woman sing. After a few minutes I tried again, but she was still singing, so I left once more.

“Now we will wait here together and speak words of Torah until she finishes her work and her singing, and only then will I enter the house.”

Rabbi Shach asked: “Could you not have entered, and as soon as she noticed your presence she would have stopped singing?”

Rabbi Isser Zalman straightened up and exclaimed: “Under no circumstances would I do such a thing. She is a widow, and her singing is an outpouring of her soul that brings her joy and comfort. Could it be that I would enter and cause her to stop singing?” And this too reflects the verse from our portion: “You shall not afflict any widow or orphan” (Shemot 22:21).

Sensitivity to Another’s Joy

On one Shabbat, Rabbi Moshe Levin, the rabbi of Netanya, a great scholar and saintly man, was returning home from synagogue. On that street cars did not travel on Shabbat, and children took advantage of the empty road to play jump rope across its width. It was impossible to pass without stopping their game. One of the people accompanying the rabbi noticed that he was patiently waiting at the side of the street and asked: “Would the rabbi like me to ask the girls to stop playing for a few seconds so that the rabbi may pass?”

The response of great Torah figures reveals how sensitive their hearts were to others, a result of their lifelong refinement of character. Rabbi Levin replied: “God forbid. This is the Shabbat delight of these little girls, jumping rope. Could I cause them to lose their Shabbat joy, even for a few seconds?”

Developing Sensitivity Through Commandments

Sadly, we have lost much of our sensitivity to the feelings of others. Would we think to delay entering our own home so as not to disturb a widow’s song? Would we wait in the street until children finished their game? This is the character work demanded of us by the Torah. The system of commandments between people is meant to cultivate these qualities of sensitivity and consideration for others.

While all commandments are divine decrees, most of them require consideration: consideration for others, for orphans, for the poor, for women, for Torah scholars, and more. The mind must always be occupied with “what does the other person feel” rather than “what do I feel.” From here comes the demand: “You shall love your fellow as yourself.”

And to reach this, our Sages taught in Pirkei Avot (2:4): “Do not judge your fellow until you have reached his place.” Every person must place a mirror before himself and ask: how would I act if I were in my fellow’s position? How would I feel? What would I hope for? What would disturb me? And then act toward others exactly in that way.

“You shall love your fellow” how is that achieved? “As yourself.” Put yourself in his place and treat him exactly as you would want to be treated. (From the book Mashcheni Acharecha, volume 2.)

עברית

עברית