Purim

Mordechai, Esther, and Vashti: What History and Archaeology Reveal

An excerpt from Rabbi Zamir Cohen’s book on Megillat Esther, exploring how history, rabbinic sources, and archaeology shed light on Mordechai, Esther, Vashti, and the Persian court.

- Rabbi Zamir Cohen

- |Updated

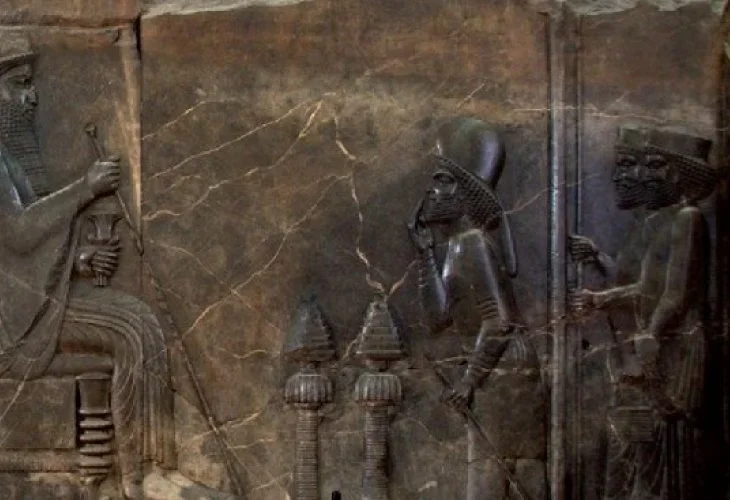

Stone relief from the Persian royal treasury at Persepolis.

Stone relief from the Persian royal treasury at Persepolis.The opening chapters of Megillat Esther describe events that changed the course of Jewish history. What begins as a royal banquet ends with the fall of one queen and the rise of another. Rabbinic sources, classical historians, and archaeological findings together shed light on these pivotal figures and their historical setting.

The Banquet and the Fall of Vashti

The Megillah recounts that on the seventh day of the feast, when King Ahasuerus was in high spirits from wine, he ordered Queen Vashti to appear before him wearing the royal crown in order to display her beauty. Vashti refused. The king’s anger flared, and on the advice of Memuchan, he decreed that Vashti would never again appear before him and that her royal position would be given to another woman more worthy than she. The king’s attendants then proposed gathering beautiful young women from across the empire, from whom a new queen would be chosen, a plan that pleased Ahasuerus and was carried out accordingly (Esther chapters 1–2).

Was Vashti a Historical Figure

Identifying queens in the Persian Empire is notoriously difficult. Scholars note that archaeological records from the Persian period almost never mention queens by name, and Persian kings were known to have many wives, further complicating identification, as discussed by Yehuda Landy in his historical analysis.

Despite this, there is an intriguing historical parallel. Rabbi Yaakov Medan points out that the mother of Artaxerxes II bore the Persian name Paroshtish or Parvashthish. When the customary removal of prefixes and suffixes is applied, a practice seen with other ancient names, the result is the name Vashti. This suggests that Vashti fits well within known Persian royal naming conventions and lends historical credibility to her appearance in the Megillah.

Mordechai and Esther Enter the Story

After concluding the account of Vashti, the Megillah introduces Mordechai and Esther. It tells of a Jewish man living in Shushan the capital, named Mordechai, who raised his cousin Hadassah, also known as Esther, after her parents died. When the royal decree to gather young women was issued, Esther too was taken to the king’s palace (Esther 2:5–8).

The text emphasizes that Mordechai lived in the citadel of Shushan, an area reserved for officials and people of status. This detail suggests that he already held a respected position before his later rise to power.

Mordechai as a Historical Figure

Rabbinic sources relate that Mordechai served as a senior officer in the Persian army, a claim supported by broader historical evidence that Jews served in Persian military units, as documented in sources such as Yalkut Ma’am Loez and the Hebrew Encyclopedia.

Modern scholarship adds another layer. Professor Michael Heltzer notes that an administrative document discovered in the Babylonian city of Sippar mentions a high official from Shushan named Marduka, who served as a royal treasurer after retiring from the army during the reign of Ahasuerus. The name Marduka closely resembles Mordechai, strengthening the case for a historical figure behind the biblical account. Similar discussions appear in studies by Edwin M. Yamauchi and in David J. A. Clines’ extensive analysis of the historical Mordechai.

The Historical Name of Queen Esther

Like Vashti, Esther’s historical identification is challenging, since Persian kings rarely recorded their wives’ names. Nevertheless, the writings of Herodotus mention Queen Amestris, the wife of Xerxes, known in Hebrew sources as Ahasuerus. Scholars note that the transformation from Amestris to Esther is linguistically plausible, with the absorption of the letter m and the dropping of the common ending, a pattern found in other ancient names.

Together, these linguistic parallels and historical records suggest that Esther, like Vashti and Mordechai, fits naturally into the known world of the Persian royal court.

Closing Thoughts

The Megillah’s narrative is not only a story of faith and salvation but also one deeply rooted in its historical context. Through careful reading of the text, rabbinic tradition, and external historical sources, figures such as Vashti, Mordechai, and Esther emerge not as abstract characters but as individuals who align closely with what is known of Persian history. This convergence of scripture and scholarship deepens our understanding of the Purim story and the world in which it unfolded.

עברית

עברית