History and Archaeology

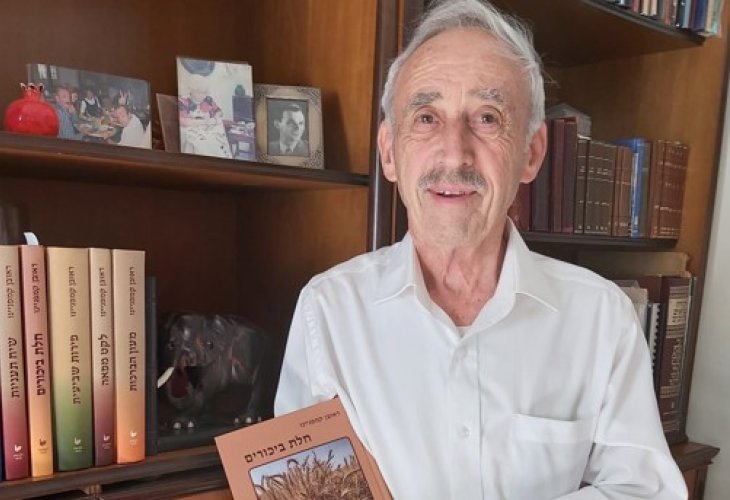

From Hidden Baby in Wartime Italy to Guardian of Jewish Heritage: The Life of Reuven Campanino

A Holocaust survivor who became a master restorer of ancient Jewish books — preserving family legacies, rediscovered texts, and sacred prayer books for future generations

When Reuven Campanino was born in 1942 somewhere in Italy, it was in the midst of World War II. His father was taken from Florence to Auschwitz, where he was murdered, and his mother handed him over as a tiny infant, to a non-Jewish family who adopted him until 1945. Even before the war officially ended, his mother miraculously managed to rescue him and immigrate with him to Israel.

“I was just a baby during the war, so of course I don’t remember anything,” says Campanino, who today lives in Jerusalem, a father, grandfather, and great-grandfather to many. “But when I was 19, my mother was invited to give testimony at the Eichmann trial. In that historic trial, a representative from every country occupied by the Nazis was asked to describe the suffering of its Jews — and my mother was chosen to testify on behalf of Italian Jewry.

“My mother was the sister of the well-known Rabbi Dr. Nathan Cassuto, who was very active in the Jewish community in Italy. She was chosen because she went through tremendous suffering and had witnessed firsthand what the Jews endured.

“That period of the trial was unforgettable for me. I felt, in a very real and powerful way, how deeply my past shaped my entire existence — and specifically as a Holocaust survivor, it awakened in me the desire to continue documenting and preserving the heritage of the Jewish people.”

From Military Intelligence — to the Mission of Saving Books

Campanino spent his childhood and youth in Kibbutz Yavneh, where he moved together with his mother shortly before the War of Independence. He later married, enlisted in the IDF, and served in Military Intelligence until the age of 40, retiring with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

At that point, his life took an unexpected turn.

“Given how deeply I was involved in intelligence work, everyone assumed I’d look for a job that required broad intellectual expertise,” he explains. “Another thing I was engaged in for many years was writing commentaries on the Jerusalem Talmud. I even published several books on it — so people naturally assumed I’d continue in academic or research-based work.”

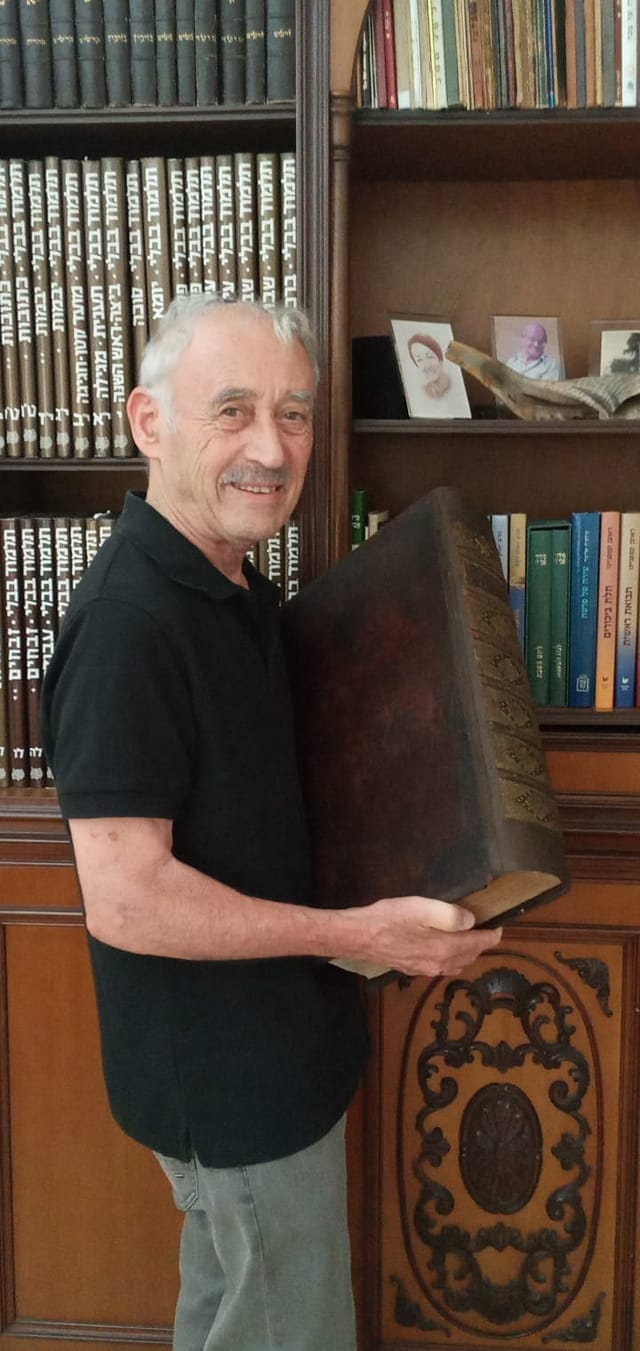

But Campanino surprised everyone. Next to his Jerusalem home, he opened a small workshop — and began devoting himself to a unique craft of restoring old books.

“There were two reasons for this,” he says. “I have always loved books, especially scholarly works, and I have also always loved working with my hands. At first, I thought about becoming a metalworker — but when the idea of restoring ancient books crossed my mind, I realized I could combine both passions. And indeed, for over 40 years now, that’s what I’ve been doing.”

He smiles as he explains that this blend of intellectual study and craftsmanship is something he inherited from his mother, who until her passing some 30 years ago worked as a math teacher and held a doctorate from the University of Rome.

“She prepared students for matriculation exams and trained teachers, but alongside that she constantly engaged in handicrafts including embroidery, ceramics, sewing, and she never saw that as conflicting with academic life. I’m very much the same way — deeply connected to both manual craft and scholarship — and that’s exactly what keeps me in this profession for so many years.”

Who brings you books — and why restore them?

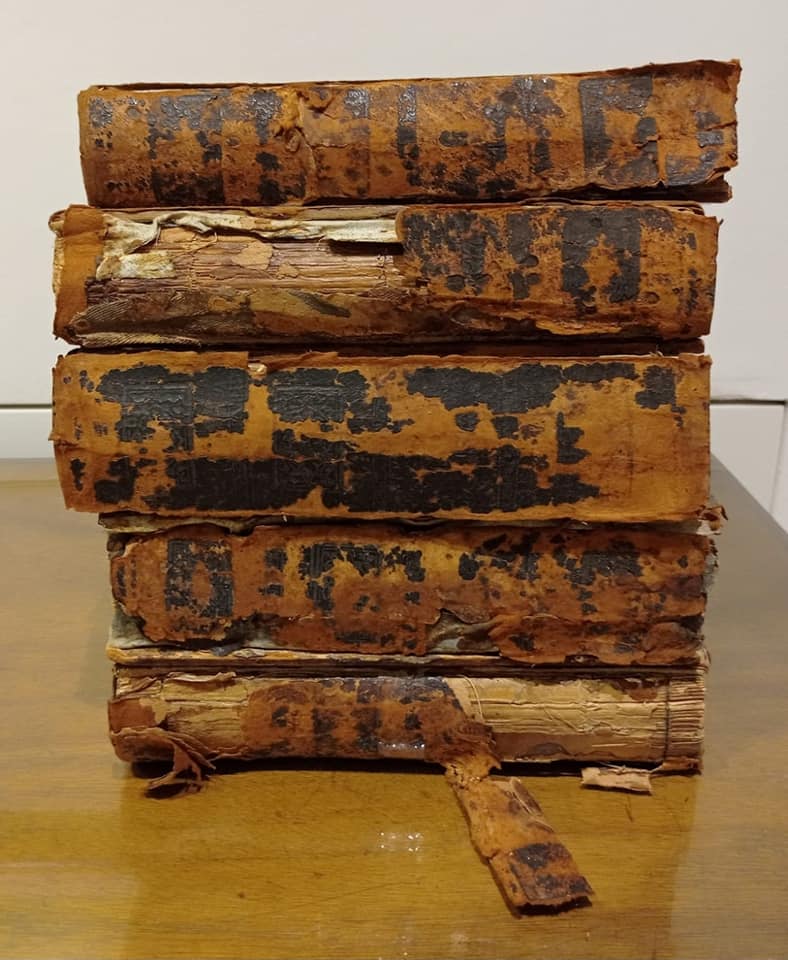

“Two types of people usually come to me,” he explains. “There are collectors of antique books — they buy them at auctions or from dealers, sometimes paying enormous sums, and they want to reinforce and preserve them for many more years.

“Then there are individuals who inherit books that passed from generation to generation. Sometimes those books have financial value — and sometimes the value is purely emotional. But they want to keep them in good condition, so they bring them to me for restoration.”

Mysteries Hidden Inside the Binding

Campanino specializes primarily in restoring bindings.

“If the original binding can be saved, I always prefer to keep it, only strengthening the corners and the spine,” he explains.

And sometimes, that process reveals remarkable surprises.

“When we’re dealing with books bound 300 or 400 years ago, there was often a shortage of cardboard — so binders used sheets of paper glued together inside the covers. That means that sometimes, when I carefully dismantle a binding, I find inside old pages containing Torah insights, prayers — and sometimes even handwritten texts.

“Sometimes it turns out those pages are much older than the book itself, and even more valuable.”

He emphasizes that he himself does not evaluate the financial worth of such findings, but often refers clients to professional appraisers.

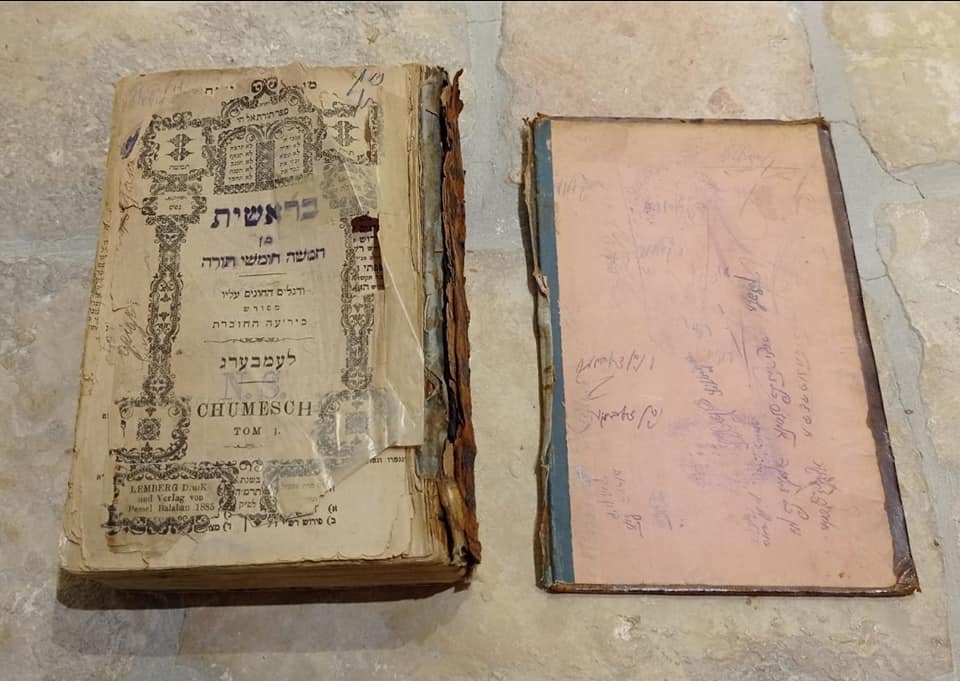

A 15th-Century Discovery Hidden in a Cover

“One day,” he recalls, “a history professor came to me with an old book whose binding was made of parchment glued to cardboard. He asked me to reinforce the cover.

“I immediately recognized that the cardboard had no value — but the parchment did. So I carefully removed it and placed it in a shallow bath of water.

“After two minutes, I saw the color of the water change. I quickly removed the parchment — realizing that something must be painted on its inner side. And I was right. When I separated it from the cardboard, I discovered a magnificent illustration of a ketubah (marriage contract).

“It wasn’t the whole ketubah — only the upper decorative section — but it was exquisitely detailed. When I called the professor, he was amazed. As a historian, he was able to identify its era based on the artistic style — and concluded that the ketubah was from the 15th century.”

Repairing Siddurim — and Survivors’ Books from the Camps

Sometimes his work also involves repairing damaged pages — especially in prayer books used daily.

“The closer the pages are to the binding, the more they wear out,” he explains. “So blessings like Modeh Ani, Morning Blessings, and Shema are often in the most fragile condition.”

For complex restoration, he sometimes sends books to a special conservation lab at the Hebrew University, where advanced equipment professionally reconstructs torn pages.

Some projects move him especially deeply. “Not long ago,” he shares emotionally, “a siddur that had been used by Jews in Auschwitz was brought to me. Many books of prayer and Torah were found after the war in attics and basements.

“Whenever I restore books like these, my hands literally tremble. I think to myself about the incredible privilege we have as Jews, to continue the eternal chain of Torah, to preserve these precious books, and to pass on our heritage to future generations.”

His Advice to Families Holding Old Books

“If you feel a special connection to a book — emotional, historical, or spiritual, it’s worth investing in restoration,” he says. “Even a book that seems beyond repair will almost always look far better after treatment.

“If there’s no sentimental attachment — if you don’t specifically want to pray from your grandmother’s tear-stained siddur, or display your great-grandfather’s book on your shelf, then restoration isn’t necessary. You can always buy another copy cheaply.

“Book restoration is for those who love memory, heritage, and nostalgia. And for them, that’s exactly why I’m here.”

עברית

עברית